The Life & Art of Canadian Painter Emily Carr

A Context

A benefit of having an art-loving mother from Canada was my exposure from a young age to art from that country. Every Christmas, my Canadian relatives would send my parents a calendar. These invariably featured reproductions of paintings by important Canadian artists. Consequently, my earliest memories of art are not of Australian art, but Canadian. There is a familiarity that comes with our experiences in childhood and our memories of them, that, however distant, are rarely lost. Over 50 years later, these memories have not been lost to me.

One of the art world’s great secrets is early 20th century Canadian art, and in particular Canadian landscape painting, are some of the finest works of art ever created. They reflect the efforts of Canadian modernists seeking new ways to represent their landscapes in a manner that was relevant to them.

There are parallels between Canadian and Australian landscape painting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Both nations were colonies of Great Britain before achieving their independence. Their early artists often painted their respective countries in a restrained, conservative and traditional manner that reflected their British heritage. They knew how to paint their landscapes for their times, but not for a modern era.

It was in Australia in the 1880s and 1890s that the Heidelberg School of artists used the natural Australian light and plain air painting to break away from the formal and romanticized approach to landscape painting which had proceeded them. Painters such as Arthur Streeton, Walter Withers, Tom Roberts and Fredrick McCubbin sought to capture Australian life, the bush, and the harsh sunlight and heat-haze that typifies much of the country.

With its vast lakes, mountains and forests, characterized in eastern Canada by the multitude of colours of its deciduous forests and in the west by mountains cloaked in tall and deep-green conifers, Canada is completely different. It took painters of the likes of Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven in eastern Canada and Emily Carr in the west in the 1910s, 1920s and beyond, to portray their extraordinary landscape in a distinct and modern way.

A Life

The geographical outlier of these forementioned Canadian painters and the only woman, was Emily Carr from British Columbia. She grew up in the city of Victoria on Vancouver Island. As an artist, she was, for decades, isolated from the modernist art movement in eastern Canada by the mass of its Rocky Mountains and the vastness of its prairies. Remote as she was, she painted iconic images of the First Nations’ culture and landscapes of her province.

Seemingly conforming to the stereotype of the eccentric artist, Emily was an individualist and non-conformist in an era when adhering to social rules and customs was expected. It’s challenging enough for those who rebel against society’s norms, let alone for an unmarried woman in the Edwardian era. But this she did.

It was in Emily’s times, and remains for many creative people who think, work and act ‘outside the square’, that they are judged, looked down upon and spoken about in disparaging ways for their apparent eccentricities, when they are not, in a wider sense, known for what they do. This was the case for Emily Carr. It was only when her talent as a writer and then as an artist was recognized, that these attitudes moderated. There are any number of people in the Canadian art community who would agree with the proposition that there is a direct correlation between the monetary value of her paintings and the esteem in which she is held. Sadly, this is often the nature of these things.

Another perception of Emily is that she was a loner. Whilst charting a course in life that saw her spend much time alone, she was not, by nature, a solitary person. During her years in Victoria, she became friends with people from diverse backgrounds and with a range of occupations, including other artists, church people, photographers, mechanics, educators, Chinese & First Nation locals, shopkeepers and the like, some life-long. Not suffering fools lightly, what they needed to be a friend was to be sincere, open-minded, kind (especially to animals) and non-judgemental. These were the exact same qualities she demanded of herself.

She was ahead of her time. In an era when First Nation’s people were experiencing rampant racism across Canada, she was embracing both them and their art, in principle and in practice. When women were supposed to marry, settle down and have children, she didn’t. And when they were expected to dress and behave in conventional ways, she wouldn’t. When animal welfare was barely an issue, she was caring for unwanted animals of all kinds on the streets of Victoria. When she saw forests being devastated by uncontrolled logging, she spoke out against it and painted what she saw. It’s tough being ahead of your time, but it was who she was.

Emily was rebellious by nature. She was also an immensely determined and resilient woman. She charted a career as an independent artist, which has its own particular set of challenges, the least of all being financial. She endured the early deaths of her parents, and later, a serious lack of support for her art. Never driving a car and determined to represent British Columbian landscapes and First Nations through her art, she travelled to remote places by any means she could, living as rough as was possible in her era. She did all this essentially alone and as a single woman. The paintings she did are as much a testament to the strength of her character as they are to her ability as an artist.

The Carr house in Government Street, Victoria in 1874.

The Carr house in Government Street in the 2000s

She was born on December 13th, 1871 in Victoria, BC., the second youngest of nine children. Her parents, well-to-do merchant, Richard Carr and her mother, (also) Emily Carr (née Saunders) owned an impressive two-storey home at 207 Government Street in Victoria. Her mother died in 1886 and her father in 1888, both of tuberculosis. Her eldest sister, Edith became her siblings’ guardian.

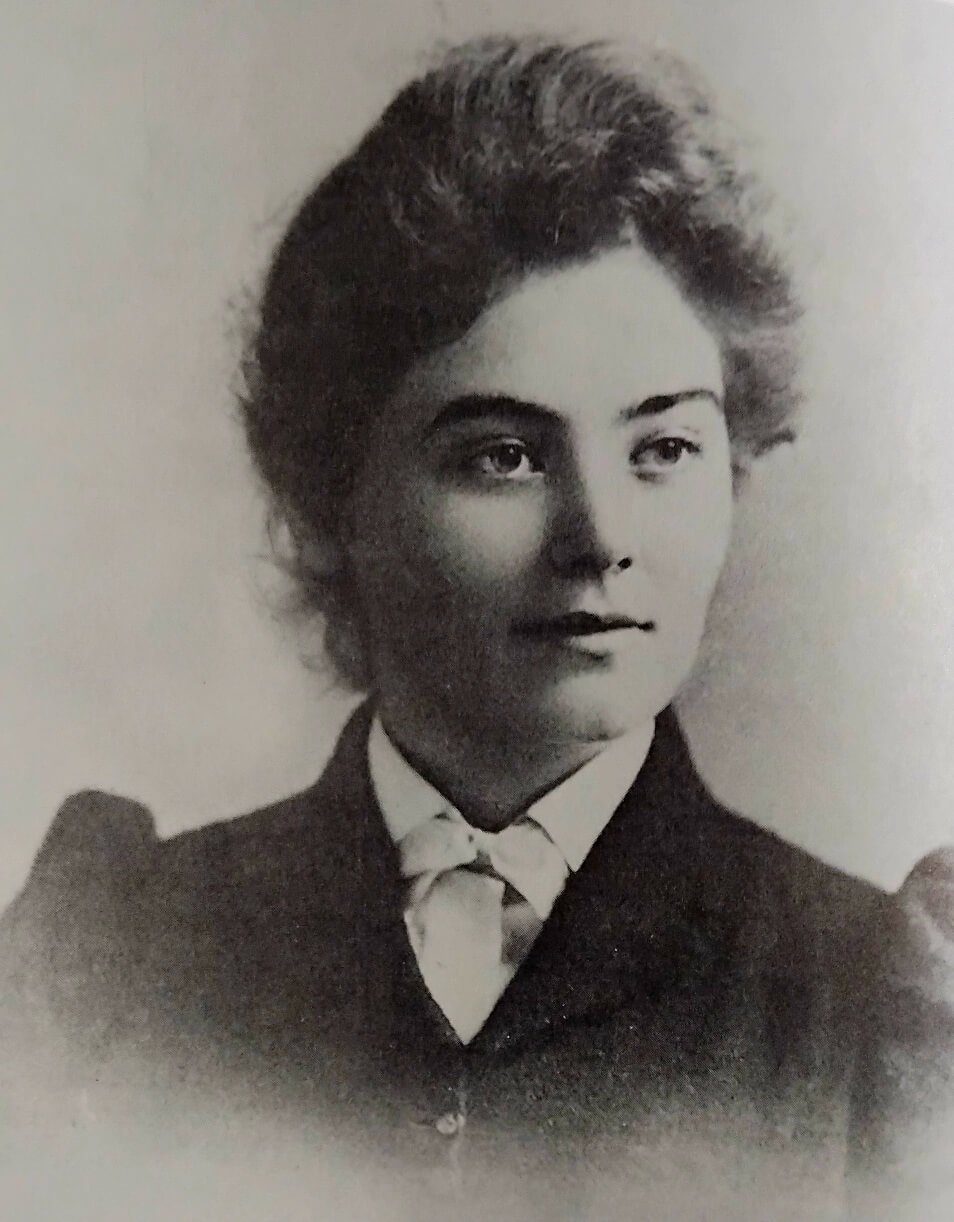

Emily in 1887.

Emily enjoyed drawing as a child. Her father encouraged her creative inclination, but it was only in 1890, after her parents’ deaths, that she pursued art seriously. At the age of 18, she travelled to San Francisco and for three years studied art at the California School of Design, learning the rudiments of drawing and painting. Returning to Victoria, she taught children’s art classes, initially in her family home and then in their barn, which also functioned as her studio.

Emily c. 1888.

In 1898 and aged 27, Emily made the first of several sketching and painting trips to First Nations’ communities on Vancouver Island’s west coast. She stayed in a village near Ucluelet, home to the Nuu-chah-nulth people, then commonly known to English-speaking people as ‘Nootka’. She was given the Indigenous name of Klee Wyck which means ‘Laughing one’. This was a huge honour as she would have experienced a Naming Ceremony there.

The five Carr sisters c. 1890. Emily is lower right. From her (clockwise) are Alice, Lizzie, Edith and Clara.

“It amused the Indians to see me unfold my camp stool, and my sketch sack made them curious. When boats, trees, houses, appeared on the paper, jabbering interest closed me about. I could not understand their talk. One day, by grin and gesture, I got permission to sketch an old mat-maker.”

Emily’s exposure to First Nations’ culture began in childhood. In the 1870s, there were almost as many indigenous people in Victoria as there were non-indigenous. She had seen their beach fires and canoes along the cliffs of Victoria’s southern coastline, only a short distance from her home. Her family’s washerwoman was indigenous. She may well have identified with them through their lifestyle and culture which appeared to be free from the restrictions and conventions under which she lived.

Emily c. 1892.

In 1899 and wanting to learn more about painting, Emily travelled to England and enrolled at London’s Westminster School of Art. Later, she lived and painted at an artist colony at St Ives in Cornwall. In 1902, her health failed and she became seriously ill. She was diagnosed with ‘Hysteria’, a diagnosis that no longer exists, but was then considered a physical illness in women. Like many people, Emily dealt with bouts of depression and other mental health challenges throughout her life. Disliking London (“unbearable … too many people, too little air”), home-sick, isolated, lacking in family support, and experiencing doubt about her art, she was overwhelmed. She spent fifteen months at the East Anglia Sanatorium, forming a few friendships there and for a time raising birds in her room. She was also subject to crude, untested and unproven experimental treatments including over-feeding and electric shock treatment. Rather than helping her, these most likely delayed her return to health.

Emily in Cornwall in 1901-2.

Emily was discharged in early 1904 and deemed cured. Resentful of her time at the sanatorium, her recovery seems more to do with her determination and strength of character than the care she received there. She remained in England for several months before returning Canada. “Sad I was about my failures, but deep down my heart sang: I was returning to Canada.”

Emily in class at St Ives in 1901-2. She is third from the left.

Emily returned to Victoria in 1904 to again teach children’s art classes. She also created political cartoons for The Week, a Victoria newspaper. In 1906 she accepted an invitation to teach in Vancouver at the Vancouver Ladies’ Art Club. Teaching women in what was essentially a social organization was not a good fit for Emily. She left it to open her own studio and teach art to younger students, working both in her studio and nearby in Vancouver’s forested Stanley Park. She was a popular teacher with her students and at one stage had upwards of seventy-five pupils. Frustrating however was the lack of time she found to paint or explore Vancouver Island as she wished.

Emily with Billie and cockatoo c. 1906.

At this stage in her painting, Emily was still searching for her expressive ‘voice’, struggling to find a way to communicate what she felt. Her painting was “captive to convention, which imposed a concern for detail, striving for the picturesque, and the concocting of effects that had nothing to do with the forest as she now felt it”. (Maria Tippett, Emily Carr: A Biography p. 73). She knew there was more to find and she was looking for it, beginning to “see a glimmer of something beyond objectivity”.

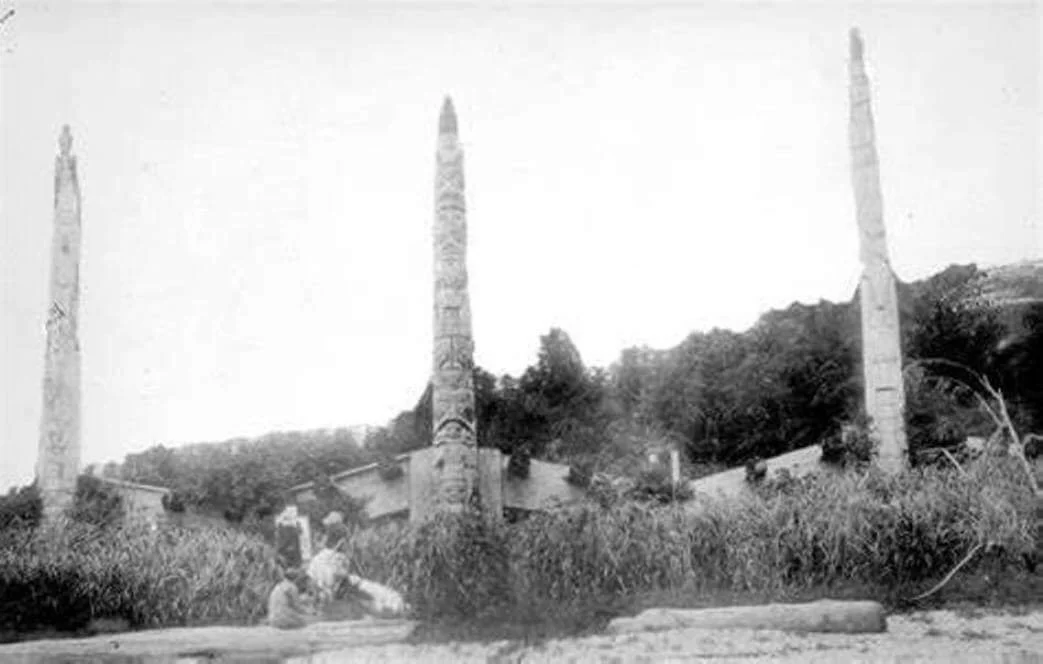

In 1907, Emily travelled to Alaska with her sister, Alice, visiting First Nations’ communities and sketching what she saw. She resolved that her artistic calling was to document all she could of First Nations’ villages, including their totems, before they completely disappeared.

“The Indian people and their art touched me deeply ... . By the time I reached home my mind was made up. I was going to picture totem poles in their own village settings as complete a collection of them as I could.”

The notion that indigenous culture would soon become extinct was a prevalent view in Emily’s era, given the cataclysmic impact of European colonization on First Nations in Canada (and elsewhere), including their contact with introduced diseases. For instance, the 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic started in Victoria and spread among the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. By conservative estimates, tens of thousands of indigenous people died from the disease within only 15 months. This incredible loss of life saw entire communities perish, and with them, vast amounts of their knowledge and traditions. For the Haida Nation for example, whose traditional territory includes Haida Gwaii (formally known as the Queen Charlotte Islands) off the coast of British Columbia and nearby Prince of Wales Island in Southeast Alaska, the death rate was over 70%. Emily visited communities on Haida Gwaii in 1912.

Following her trip to Alaska, she returned to Vancouver and reopened her studio. She then, both in 1908 and 1909, travelled up Vancouver Island’s northeast coast to sketch and paint at indigenous communities at Campbell River and at Alert Bay on Cormorant Island.

In 1910, aged 39 and wanting to further her knowledge of modern art, she returned Paris with Alice to study. She was dissatisfied with the gentle style of watercolour painting she had studied on her earlier trip to England, and had heard of ‘the new art’.

“I wanted now to find out what this ‘New Art’ was about.”

The new art she sought was post-impressionism, a predominantly French art movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905. It was a reaction against impressionist painters’ emphasis on the depiction of naturalistic light and colour. It placed greater importance on paintings having abstract qualities and using symbolism. It was more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort forms, and use unnatural or modified colours.

Emily arrived in Paris with a letter of introduction to modernist painter, Harry Gibb. She took lessons from him, and he encouraged her to adopt a more vibrant colour palette in her painting. He recommended she take art classes at the well-regarded Académie Colarossi, however as she could not speak French, she found these unsatisfactory. She was also older than the other students, the only female in the life class, and felt uncomfortable in the presence of male nude models. After a month at the Académie Colarossi and at Gibb’s suggestion, she met Scottish artist, John Duncan Fergusson. He had embraced the les Fauves style of bold colour and broad brushwork, and she took lessons from him in a more sympathetic environment.

Whilst in Paris, Emily became ill again, as she had on her earlier trip to Europe. This was largely from the stress of overwork and anxiety about the progress she believed she should have been making, but felt she wasn’t. She entered an infirmary, remaining there for about six weeks. She convalesced in Sweden with Alice before returning to Paris. She studied with Gibb again, before travelling into the French countryside to sketch and paint. It was around this time she met and studied with New Zealand born painter, Frances Hodgkins. A modernist artist, her paintings emphasized abstracted and simplified forms with a strong emphasis on colour.

In 1912, Emily returned to Canada after 18 months in Europe. Having received lessons from modernist painters, incorporated her learnings into her art, and ‘done the journey’, she had matured as an artist and found her ‘voice’ as a painter. She now had confidence in her ability to paint British Columbia’s First Nations’ communities and landscapes.

She rented a studio in Vancouver and organized an exhibition of seventy watercolours and oils representative of her time in France. These displayed her new style of painting with its bold and vibrant colours and simplified imagery. Her work attracted attention in the press, both words of praise and criticism. Responding to criticism, she wrote in the British Columbian newspaper The Province, that “a picture should be more than meets the eye to the ordinary observer. … Art is art, nature is nature, you cannot improve upon it. Pictures should be inspired by nature, but made in the soul of the artist, it is the soul of the artist that counts.”

Later in 1912, she took a sketching trip to First Nations’ villages in Haida Gwaii, the Upper Skeena River and Alert Bay where she recorded the art and people of the Haida, Gitxsan, Tsimshian and Kwakwala nations. She was particularly fond of Alert Bay and its people and did many of her well-known oil paintings there.

Emily on the beach at T’anuu (aka Tanoo) on Haidi Gwaii, British Columbia in 1912. She used photographs and sketches from this trip for paintings such as Tanoo, Q.C.I., 1913, which she completed in her studio.

Tanoo, Q.C.I., 1913

In April of 1913, Emily held an exhibition of her paintings of First Nation’s Canada in Vancouver. It included almost two hundred sketches, watercolours and oil paintings of indigenous British Columbia, representing fourteen years of painting, from Ucluelet in 1898 and 1905, to her most recent trip in 1912. The exhibition received a modest reaction. Some reviews were positive, one British Columbian newspaper, The Province, calling it ‘a very valuable record of a passing race’. But the majority were negative.

“My pictures were hung either on the ceiling or on the floor and were jeered at, insulted; members of the ‘Fine Arts’ joked at my work, laughing with reporters. Press notices were humiliating. Nevertheless, I was glad I had been to France. More than ever was I convinced that the old way of seeing was inadequate to express this big country of ours, her depth, her height, her unbounded wideness, silences too strong to be broken, nor could ten million cameras, through their mechanical boxes, ever show real Canada. It had to be sensed, passed through live minds, sensed and loved.”

She also gave a public talk titled Lecture on Totem Poles about the Aboriginal villages that she had visited. It ended with her mission statement:

“I glory in our wonderful west and I hope to leave behind me some of the relics of its first primitive greatness. These things should be to us Canadians what the ancient Briton’s relics are to the English. Only a few more years and they will be gone forever into silent nothingness and I would gather my collection together before they are forever past.”

She had been hoping that the provincial government would exhibit her work and support her financially to carry out more trips to First Nations’ villages. This was not to be, a report to the British Columbia’s provincial museum stating that the paintings were “too brilliant and vivid to be true to the actual conditions of the coast villages” and that her painting was “laid on with a heavy hand”. (Maria Tippett, Emily Carr: A Biography p. 110).

Emily was never shaken in her conviction of the importance of her work, but in practical terms, believed that she would not be able to support herself through it. She had already made plans to return to Victoria and did so following the exhibition.

“Nobody bought my pictures. I had no pupils; therefore, I could not afford to keep on the studio. I decided to give it up and to go back to Victoria.”

Emily at Simcoe Street in 1918.

In what was a moment of good fortune, her family property in Government Street had only recently been subdivided. Some blocks were sold and five, including the family house, divided amongst the sisters. Hers was at 642-646 Simcoe Street, close to the house in which she had grown up. She had four apartments built, three to rent and a fourth for herself. For the next 15 years, she managed ‘The House of all Sorts’, for a time as a boarding house.

Arbutus Tree, 1922. This is one of a handful of paintings by Emily she did whilst operating ‘The House of All Sorts’. Responsible for everything there (‘I must be owner, agent, landlady and janitor’), it is remarkable she found the time and energy to paint at all.

To support herself, Emily also raised and sold chickens, rabbits and English sheepdogs, and cared for stray animals.

“One old sheepdog was always in the house with me, always at my heels. He was never permitted to go into any flat but mine. There was, too, my great silver Persian cat, Adolphus. He also was very exclusive. People admired him enormously, but the cat ignored them all.”

Emily with her pet monkey, Woo c. 1925.

She built a kiln to fire the pottery she made and sold, decorated with First Nations’ designs, and made and sold hooked rugs, also featuring indigenous designs. She painted a few works in this period drawn from local scenes, including the cliffs on the southern tip of Victoria (the Dallas Road area) and the city’s sprawling Beacon Hill Park, both close to her home.

Pottery made by Emily and displayed in the home of Kate Mather. She as a craftswoman who operated a summer gift shop in Banff, the resort town in Banff National Park in Alberta. She was an outlet for her pottery.

Over time, Emily’s work came to the attention of several influential and supportive people. In 1927, Eric Brown, Director of Canada’s National Gallery visited her in Victoria. She was invited to exhibit at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa as part of the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern. Emily showed 26 paintings, along with pottery and rugs. The exhibition, which was largely of First Nations’ art, also travelled to Toronto and Montreal.

The Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art at the National Gallery of Canada in 1927. Shown are two of her paintings and a hooked rug (centre left)

Emily made the trip east for the exhibition. In Toronto she met members of the Group of Seven, Canada’s most important modernist painters. Their landscapes resonated with her intensely. After what must have seemed like a lifetime of working alone, their acceptance of her as a fellow painter and praise of her work was a revelation. Aged in her mid-fifties, her period of artistic isolation of the previous 15 years came to an end.

Lawren Harris of the Group became an important mentor and friend. Seeing his work, she exclaimed, “Oh, God, what have I seen, where have I been?” Their correspondence allowed her to discuss, for the first time, matters of art and spirit with a painter whose work resonated deeply with her. “You are one of us”, he told her.

Her encounter with the Group of Seven led to one of her most prolific creative periods and the painting of many of her most notable works. Over the next few years, she produced a large body of work in charcoal, watercolour and oil paint. She made return trips to Haida Gwaii. She reviewed many of her earlier paintings and reworked them with a strength, boldness and grandeur that reflected the power and importance of their subject matter. Some of these, such as Big Raven are her most iconic works.

Big Raven, 1931

Emily’s artistic direction over the following years was influenced by her love for nature and solitude, and her time spent experiencing the natural environment on trips to remote parts of Vancouver Island. It was influenced by Lawren Harris’ work and his suggestion that she seek an equivalent for the totem poles in west coast landscapes. And it was influenced by Seattle painter, Mark Tobey. She studied with him and was introduced to cubism, where objects are broken down to geometric shapes and shown from different angles all at once. It focused on structure and form rather than realistic details. Emily embraced this approach, helping her to reveal “the hidden thing which is felt rather than seen, the ‘reality’ of which underlies everything”.

Drawing by Emily based showing her learnings from her course in Cubism by American artist, Mark Tobey in 1928.

Kitwancool Totems, 1928. This painting shows Emily applying lessons learnt on Cubism from Mark Tobey.

Representing the forests and landscapes of Canada’s west coast became the second great theme of Emily’s artistic life. She took to painting the hills, mountains, forests and trees of Vancouver Island. She made sketching expeditions along the island’s coastline and into forests readily accessible from Victoria. She travelled to the Coast Mountain area of Pemberton, north of Vancouver. It was in these places that she felt her spiritual connection to the landscape and felt the living presence of God. Whilst not a conventionally religious woman, she believed that she could express the joy and wonder she felt in the natural world through her art.

Emily participated in the Ontario Society of Artists exhibition in Toronto in 1929. The Indian Church, Friendly Cove, one her finest and most recognized works, was shown there and purchased by Harris.

The Indian Church, Friendly Cove, 1929

Her art was soon to be exhibited in other Canadian cities and in the United States. In 1930, after sending paintings to a Group of Seven exhibition in Toronto, she travelled on to New York and visited galleries there. That year, although she hated “like poison to talk”, she gave two public lectures on modern art. She emphasized the importance of distortion, which “raises the thing out of the ordinary seeing into a more spiritual sphere”.

Emily with members of her animal family c. 1934.

In 1933 and in her early sixties, she bought an old caravan and fitted it out for sleeping, cooking and working. For the next four summers, she had it had towed to locations around Victoria to explore landscapes and sketch.

Emily with her caravan and friends in 1934.

Emily sold her ‘House of All Sorts’ in 1936. She bought a cottage nearby, at 316 Beckley Street. It was there, in 1937, she suffered her first heart attack. This was followed by a second in 1939. In 1940 she went to live with her sister, Alice on land that had once been her family’s vegetable garden. That year she had a stroke. She continued to sketch and paint, but limited in her ability to do so, increasingly used writing as her creative outlet. “One approach is cut off; I’ll try the other. I’ll ‘word’ these things which during my life have touched me deeply.”

Emily had written throughout her life and had kept a journal since 1927 (published in 1966 as Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr) following her meeting with the Group of Seven. Her first book, Klee Wyck, collection of short stories based on her experiences with First Nations’ Canadians, was published in 1941. That year, it won the Governor General’s literary award in the field of general literature. The Book of Small, published in 1942, is a collection of 36 short stories about growing up in Victoria. Her other books were published after her death.

Her final painting trip was in August 1942, at Victoria’s Mount Douglas Park. From this she produced her final works, Cedar Sanctuary and Cedar.

Cedar, 1942

Cedar Sanctuary, 1942

In 1942, aware that her health was in decline, Emily donated 170 paintings to the Vancouver Art Gallery. She then donated another 500 paintings to be sold to benefit a new scholarship to help young artists in British Columbia.

Emily c. 1936

In 1944, she held the only successful commercial exhibition of her career, in Montreal, selling 57 of the 60 paintings on show. While happy with the result, she was not well enough to attend.

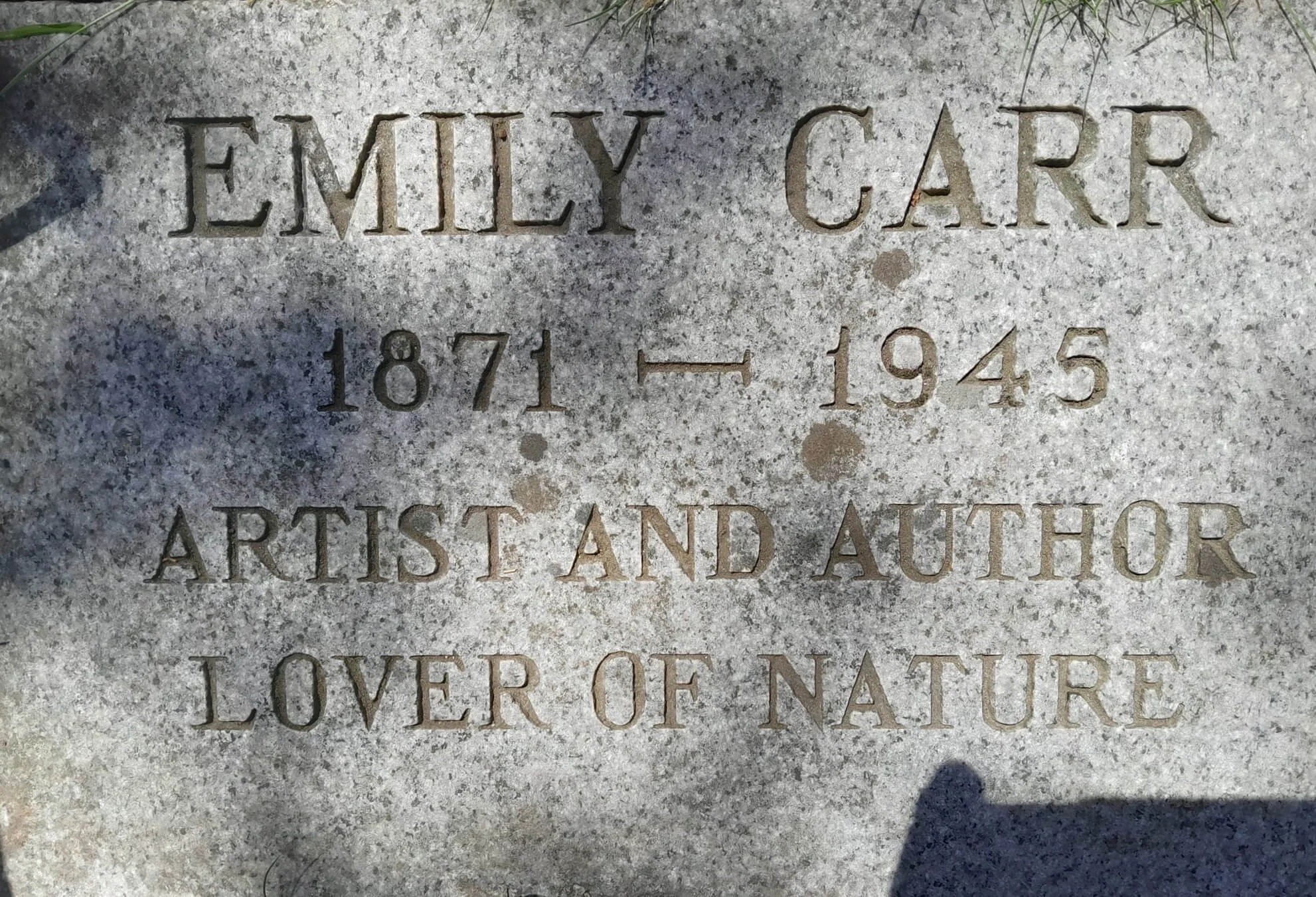

Emily died in Victoria on March 2nd, 1945 aged 73 at the James Bay Inn. She was buried at Victoria’s Ross Bay Cemetery. By the time of her death, she was receiving the recognition she so justly deserved. She is now recognized as being one of Canada’s most important painters and British Columbia’s greatest painter.

Like all great artists, Emily and her art were in a constant state of evolution. She was tenacious in her desire to find new ways to represent the subjects that inspired her. Had she painted in the middle period of her life or lived another 20 years, what else would she have done? A question without an answer.

Emily Carr left a remarkable legacy in art. Her paintings of First Nations’ villages and their totems form a vital record of aspects of Canada’s First Nations’ history. Her representations of British Columbia’s landscapes are an extraordinary demonstration of an artist’s ability to be moved by what they see and interpret it in a way that is new, accessible and beautiful. She lived every day as if it might be her last, challenging herself again and again to be the person she believed she should be. Whatever and whoever she was, she demanded more of herself than she did of others. It was a challenging life and one well-lived.

Art by Emily Carr

Emily was a prolific and wholly dedicated artist. Art was her vocation and she followed its calling. Considering she painted little between 1913 and 1927, the variety and diversity of her art, and the shear amount she produced, is stunning. For this gallery, I have chosen her works that cover the span of her active years as an artist and that give a sense of the diversity of her work. And what I have chosen appeals to me. But as you scroll through these paintings and drawings, keep in mind that this is just a fraction of her art. There is so much more to be seen and it is every bit as good as what is here.

Snowdrops, c. 1894

Victoria Sketchbook, 1896

Chrysanthemums, c. 1900

Indian Reserve, North Vancouver, c. 1905

Self Portrait with Friends, c. 1907

Alert Bay Mortuary Boxes, 1908

Seated Girl, 1909

Wood Interior, 1909

French Landscape, 1911

Brittany Kitchen, 1911

Skidegate, 1912

Totem Poles, Kitseukla, 1912

War Canoes, 1912

Old Indian House, Northern British Columbia. Indians Returning from Canneries to Guyasdoms Village, 1912

Totem Mother, 1928

Kitwancool, 1928

Queen Charlotte Islands Totem, 1928

Mrs Douse, Chieftainess of Kitwancool, 1928

The Great Eagle, Skidegate, B.C., 1929

Three Totems, 1929-1930

Untitled (formalized tree forms), 1929-30

Untitled, 1929-1930

The Raven, 1929-30

Vanquished, 1930

Friendly Cove, c. 1930

Totem Forest, c. 1930

Zunoqua, 1930

Tree Trunk, 1931

Strangled by Growth, 1931

Red Cedar, 1931

Forest, British Columbia, 1931-32

Tree (spiralling upward), 1932-33

BIue Sky, 1932-34

Wood Interior, 1932-35

Lillooet Indian Village, 1933

Scorned as Timber. Beloved as the Sky, 1935

Untitled (Clover Point from Dallas Road beach), c. 1934-36

Untitled (Wiffen Spit near Sooke), c. 1935-36.

Overhead, 1935-36

Forsaken, 1937

Above the Gravel Pit, 1937

Three Mature Trees, 1939

Sombrerness Sunlight, 1940

Masset Bears, c. 1941

A Skidegate Pole, 1941-42

The following is a list of Emily Carr’s published works. All quotes are taken from these unless otherwise noted.

The Book of Small

Fresh Seeing: Two addresses

Growing Pains: The Autobiography of Emily Carr

The Heart of a Peacock

The House of All Sorts

Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr

Klee Wyck

Modern and Indian Art of the West Coast. Supplement to the McGill News

Note.

*There are many fine books on the life and art of Emily Carr and from which I have drawn from for this piece. Maria Tippett’s Emily Carr: A Biography (1979) in particular is an outstanding record of her life and I acknowledge it as a major source.

Finally…

Thank-you to Shirley Kasper for her knowledge and insights into the life of Emily Carr, and to Jeremy Beck, Jill Kavanagh and Tamsin Ong for reviewing this writing.