Canadian Landscape Painter, Tom Thomson

There are four seasons in the world, but there are only two in my mind—painting and no-painting.

(Tom Thomson journal entry, March 18, 1917)

Together with the British Columbian painter Emily Carr, Ontario born Tom Thomson was one of Canada’s most important artists. Largely unknown outside of Canada, his name, like Carr’s, looms large over 20th century Canadian landscape painting.

Tom Thompson c. 1904

In the 1910s, for virtually the entire time Emily Carr had forsaken painting through a lack of support for her work, Tom Thomson was pushing the boundaries of Canadian landscape painting. And yet by the time Carr had begun to paint again in the late 1920s, he had been dead for over 10 years.

Thomson was born in 1877 near Claremont, Ontario, northeast of Toronto on August 5, 1877 into a large farming family. He died 39 years later in Algonquin Park in southern Ontario. Disappearing during a canoeing trip on July 8, 1917, his overturned canoe was found that day and his body discovered eight days later. The cause of death was recorded as accidental drowning.

Tom Thomson c. 1898

Thomson was strong-willed, determined, independent and resilient. Developing a love for the outdoors at a young age, he enjoyed hiking, hunting, fishing and canoeing. This affection for and familiarity with nature and the outdoor life grew as he matured, as did the pleasure its solitude offered him. For Thomson, like Emily Carr, this seems to have been a necessary requirement to find the awareness needed to paint what they did.

He had initially worked as a commercial artist in Seattle and later, Toronto. It was there, in the early 1910s, that he began to paint seriously. It was also in Toronto that he met and became friends with the young, energetic and visionary painters who would form Canada’s most important assemblage of artists, the Group of Seven. He was to influence their painting as they did his.

c. 1900

Thomson was initially doubtful of his own ability to paint and shy to show his work. Incredibly, it was as late as 1914, just three years prior to his death, that he, with the encouragement of artist friends, became a full-time artist.

During his short career, Thomson produced about 400 oil sketches on small wood panels and about 50 works on canvas. The smaller sketches were typically done en plein air. The larger canvases were completed in his studio—a shack on the grounds of the Studio Building, a low-rent artists’ enclave in Rosedale, a suburb of central Toronto. Almost all were based on what he saw and felt in Ontario’s sprawling Algonquin Park, about 290 km north of Toronto.

The Studio Building in Severn Street, Toronto.

Tom Thomson's home at the rear of The Studio Building c. 1915. This was his Toronto home from 1914 until his death.

Established in 1893, Algonquin Park is the oldest provincial park in Canada and in an area of transition between northern coniferous forests and southern deciduous forests. This unique mix of forest types and the wide variety of environments found there allows it to support an enormous diversity of plant and animal species. Thomson first visited Algonquin Park in 1912. Entranced by the beauty of its lakes, skies, rivers, forests and landscapes, he returned to it repeatedly, to fish, camp and paint.

At Tea Lake Dam c. 1915

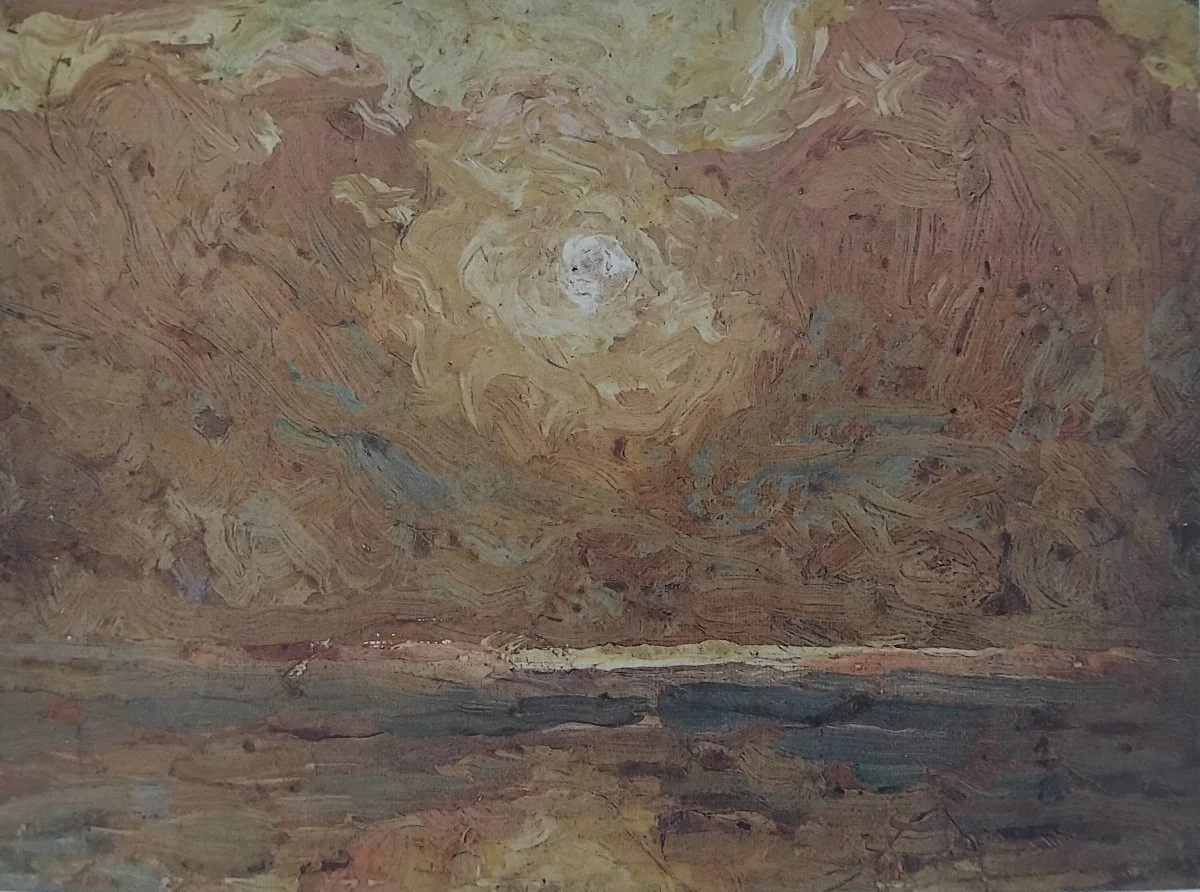

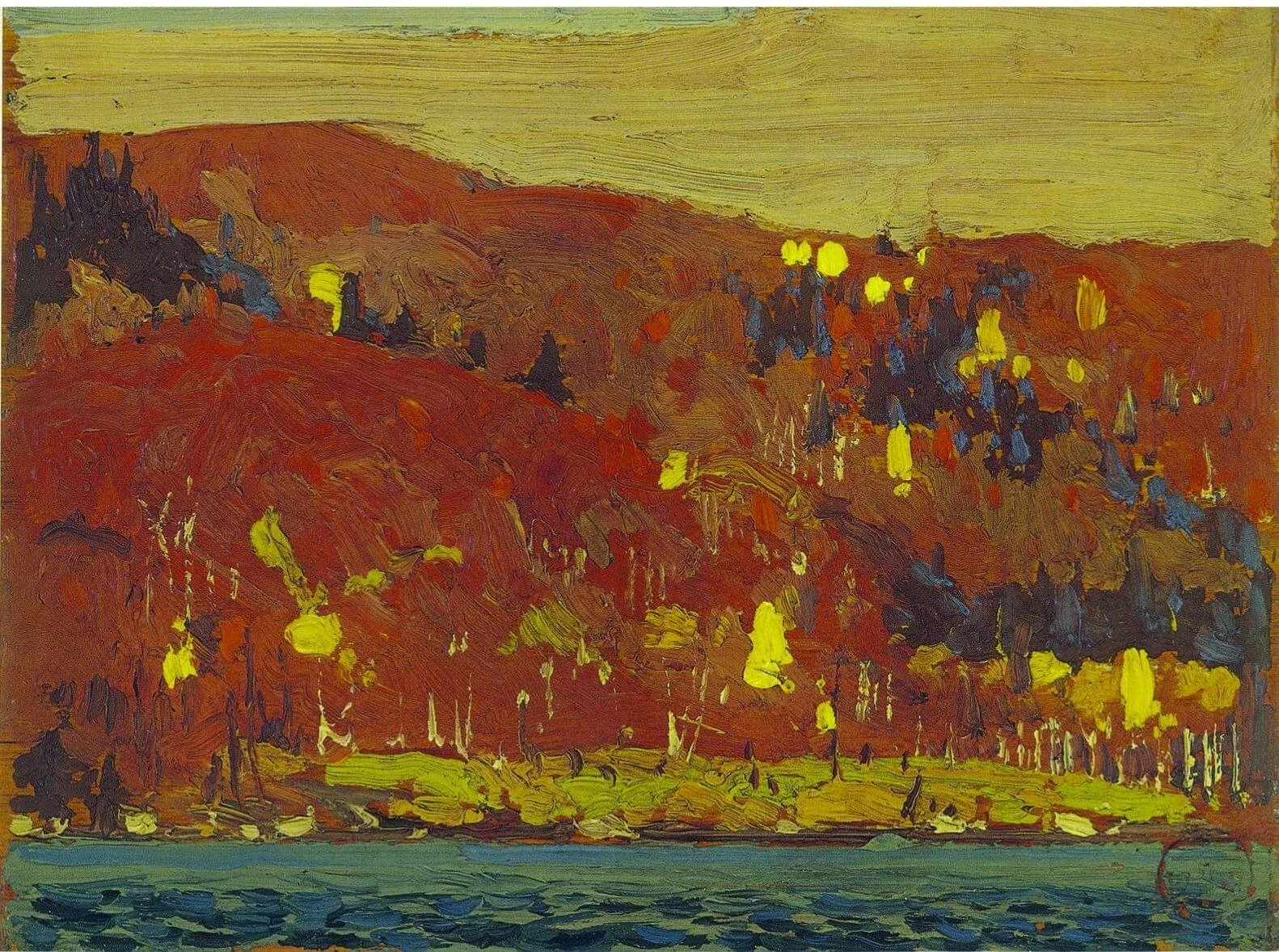

Thomson’s use of broad brush-strokes and bold colours, applied with a liberal application of paint, could have been considered audacious had they not been so effective in capturing the rugged beauty of the place he loved. Portraying the moods of changing seasons, he did not hesitate in using colour for contrast and impact in the most dramatic of ways. This is seen in his depiction of the brilliant reds, oranges and yellows of the trees and forests of Algonquin Park in autumn. Yet he was equally able to show the subtle beauty and serenity of the same places when they were not a blaze of colour, highlighted in his portrayal of the lakes that dot the park and the skies above. Some of these are painted with a complex mix of understated colours applied in dots and dabs. Others are represented by long bold lines of paint. All achieve what he was endeavouring to represent; an acknowledgement and celebration of the extraordinary beauty that surrounded and enveloped him.

c. 1915

Of particular note are his skyscapes. In some works, the sky is the focal point, rather than an accompaniment to a landscape below. He painted the most threatening and violent of storms, skies full of reds and oranges from dynamic sunsets, and others overflowing with of the most beautiful and fully formed clouds of whites, creams and greys. Had he only painted skyscapes, he would still have been lauded for the colour and the composition of his works.

Thomson was able to capture the moods of Canadian landscapes in ways that none before him ever did, and few, if any, have achieved since. By the time of his death, he was painting prolifically, and a master of his craft.

Thomson died at a time when his art was just beginning to be recognized. Whilst this was prior to the formal establishment of the Group of Seven, he is often considered an unofficial member. His art is typically exhibited with the Group.

His premature death was a huge loss for Canadian art. He had become such a proficient a painter so quickly; one wonders where his painting would have taken him next. It was a tragedy for all who knew him, including his fellow artists who lost an inspiring colleague and a great friend. It prompted a clarification of their vision for Canadian art, strengthening their resolve and giving rise to the formation of The Group of Seven.

Memorial cairn at Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park, Ontario.

The art of Tom Thomson, along with that of Emily Carr and the Group of Seven, propelled Canadian landscape painting into the modern era. Their paintings are a celebration of that landscape, rather than being just a reflection of it, as was the case prior to them. They are diverse in their composition, style, use of colour and the like, but what they share is the artists’ delight in the landforms of Canada and the nature they support, and an overwhelming desire to represent them. The art those painters created is a gift to all Canadians, and to those everywhere who enjoy fine landscape painting.

Art by Tom Thomson

View from the Window of Grip Ltd, c. 1908

Marsh, Iake Skugog, c 1911

Drowned Lake, 1912

Northern Lake, 1912-13

Thunderhead, 1912-13

Sky; The Light that never was, 1913

Morning Cloud, 1913-14

Grey Day in the North, 1913-14

Canoe Lake, 1914

Twisted Maple, 1914

Windy Evening, 1914

Split Rock Gap, c. 1914

Byng Inet, Georgian Bay, 1914-15

Autumn's Garland, 1915-16

Canoe Lake, 1915

Evening, 1915

CIouds; The Zeppelins, 1915

Lightning Canoe Iake, 1915

Late Autumn, 1915

Marguerites, Wood IiIies and Vetch, 1915

Northern Lights, 1915

A November Day, 1915

Petawawa Gorges, 1914-15

Spring Ice, 1915

OpuIant October, 1915

Red and Gold, 1915

The Rapids, 1915

Sunset, 1915

Winter Morning, 1915

The Birch Grove, Autumn 1915-16

Spring Ice, 1915-16

Sunset, Canoe Lake, 1916

Sunset, 1916

Spring, Canoe Iake, 1916

Petawawa Gorges, 1916

Northern Lights, 1916

Summer Clouds, 1916

The West Wind, 1916-17

White Birch Grove, 1916-17

The Jack Pine, 1916-1917

The Pointers, 1916-17

The Fisherman, 1916-17

The Drive, 1916-17

Dark Waters, 1917

Early Spring, 1917

Path Behind Mowat Lodge, 1917

Spring in Algonquin Park, 1917

Sunset, Canoe Iake, 1917

The Rapids, 1917