Who was Merric Boyd?

“To me, Merric was very much, by the time I met him, like Quixote. He was an exotic sort of person who really had had a life. There was I feel a tremendously sad dimension to Merric. I feel that no one’s really described him as he could be described. ”

“Mummy said to me once, ‘You know, your father is a totally different man to what he was when he was young’. I’ve often thought about the effect of epilepsy on Merric’s life. And also for my mother, not knowing when it was going to come. ”

“Mr. Boyd would sometimes come into the house when I was there, but he was usually in his studio. This was in 1926; not long before the fire, and before he got sick. He was a healthy man in those days. He was perfectly all right when I knew him. I know the fire was a tragedy for the Boyd family. ”

I’ve spent well over 30 years of my life researching and writing about the Murrumbeena Boyds. I started in 1988 and I’m still doing it now. At the centre of the Boyds world at Murrumbeena was Open Country and the centre of Open Country was Merric and Doris Boyd.

Merric, Martin and Penleigh Boyd c. 1900.

Merric at Dookie Agricultural College in 1906.

Doris Boyd was a talented artist, a woman of great intelligence, a great listener, and devoted wife and mother. She was universally liked and respected by all who knew her, from close up and afar. She fed, clothed and protected her children with deep and tireless love and devotion. She was complex, but she wasn’t complicated. The same could not be said for Merric.

Phyllis Boyd spoke her words about Merric to me many years ago and they have stayed with me. I’m not sure how sad he actually was, but I understand her belief that there was a sad dimension to him. I thought that one day, I’d have a crack at describing Merric Boyd, his ‘sad dimension’ and his ‘sad life’. This is my attempt.

Merric Boyd in his studio at Open Country in 1914.

Open Country c. 1917.

A good starting point is to acknowledge that nobody really knows what’s happening inside someone else’s head. Consequently, the only person who can accurately describe how Merric felt; happy, sad or indifferent, is Merric and that can’t be done. Another is to recognize that people are not a single dimension. They are complex and frequently full of contradictions. One day they can be cruel and the next day, kind. Open minded today and judgemental tomorrow. They can be all of these and then much more. So to describe Merric by simple explanation is not possible and could never do him justice. Like all of us, he was many things.

Phyllis met Merric in 1952 after she and her husband, Merric’s second son, Guy came to Melbourne from Sydney. They lived at Open Country for about a year and a half before buying a home in Oakleigh.

Doris Boyd c. 1920.

Merric Boyd in 1917.

The Merric Boyd that Phyllis described in 1989 had been living with epilepsy for about 25 years. By 1952, he was a shadow of his former self. Impacted by years of tonic-clonic seizures, his physical and mental health were greatly compromised. The fit and energetic man he had been was gone. He was inward looking, unable to carry out a normal conversation and often unable to identify his grandchildren. Thus, when Phyllis met him, doubtless there appeared to be, through ageing and illness, a degree of sadness to him. A lot of people in older age have lost much of their life and vigour and could be said to be at a sad stage of life. But it does not mean that they were always sad or that they had a sad life. It therefore does not define their life; it may be describing only part of it.

It also should be noted that Merric endured tragedies in his life that would sap the joy from anyone. Chief of these were the premature deaths of two of his three brothers. His eldest brother, Gilbert died in 1896 in a horse-riding accident, aged nine years. Twenty-seven years later, in 1923, his second brother, Penleigh died in a car accident, aged 33 years. There is a 27-year gap between these tragedies. For family members, emotionally, a 27-year gap is in the blink of the eye. How Merric endured this, I do not know, but he did. In my own life I have known people to lose two children, and in my own family, three. These things can break people.

Merric Boyd in 1917 with Doris and Lucy Boyd.

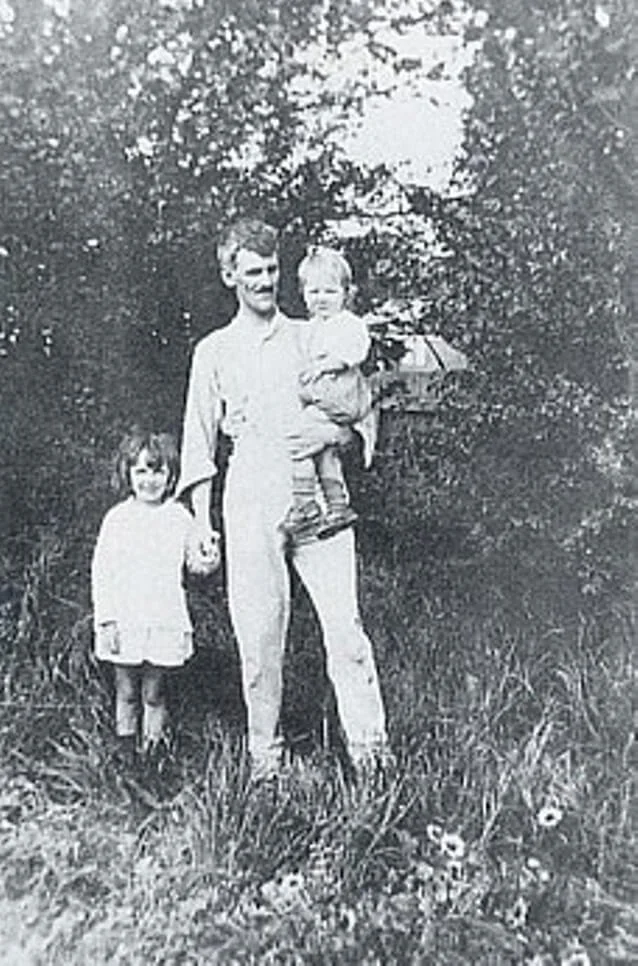

Merric Boyd at Open Country with his children, Lucy and Arthur c. 1922.

I was not yet two years old when Merric died and living in West Footscray. Our paths did not cross, in time or place. But I have read a lot about Merric and spoken with many people who knew him, from close up and from afar. Having contemplated Merric’s character, I realized that his family members could speak of him far better than I. ‘Knowing’ Merric as I do, their words rang true to my understanding of the man. This is what they said:

Merric was Unconventional

“What was wonderful about him was the way he was completely unconcerned, or unaware, of what people thought of him. He’d sometimes say things that people thought were really outrageous, but weren’t to him. I think I’m a bit like Daddy in some ways; I can get wild and woolly, but I can shut up pretty quickly! I can see a lot of my father in me. ”

“We went to a restaurant once in the city somewhere. It wasn’t a very fancy place. We all had ice-cream, and there was a bottle of tomato sauce on the table. Daddy picked up the bottle and smothered his ice-cream with sauce. He lapped it up and thought that it was wonderful. Sometimes I think he was aware of doing things differently and didn’t care, and other times he was just unaware. I think it was a little bit of both. ”

Merric Boyd at Open Country with his children, Lucy and Arthur c. 1922.

Merric was Polite

“Aunt Helen told me that he always wanted to do the right thing by ladies. He had this great sense of dignity and respect for ladies. She told me about one time when she came to see us at Murrumbeena. When it was time for her to leave, Daddy wanted to see her off at the station. He said, “I’ll see you to the station”, because that was what the gentlemen did in those days. She said, “No, Merric. I’ll be perfectly alright; I know the way. Please don’t worry.” He could see he’d get nowhere with her because she, like him, was terribly strong-willed. She went on her own and when she arrived at the station, there was Daddy waiting for her. He’d taken a side street to the station to see her off on her train. He wanted to do the correct thing.

He always wanted ladies to go ahead of him. One time, a woman was apparently behind him when he was getting onto a train. He said, “You go first.” She didn’t want to go first. He wouldn’t go in until she got in and she wouldn’t go in until he got in. They were both left stranded on the station. ”

“Being courteous to people; for example always offering to carry the shopping for people if you met them in the street, was very important to Merric. He’d advise us whenever we were going anywhere. He’d say, “Now remember, always be polite to ladies. Never sit whilst a lady stands. Always offer your chair to someone if they are standing”. These things were driven into us. ”

Merric Boyd with daughter, Lucy c. 1921. To the right is his brother, Penleigh and at the right, their father, Arthur Merric.

Merric was Religious

“Merric and Doris were both deeply religious. I think they found Christian Science very helpful. We were advised by Doris, when asked our religion, to always give it as Church of England, to protect ourselves. Otherwise we were going to find ourselves having to explain Christian Science. When we weren’t old enough to do that, what was the point? ”

“He was always deeply religious, as was his mother. He decided he wanted to be a clergyman and was sent to St. John’s Theological College. There is a story about him having an argument with the Dean over a fly. There was a blowfly in the hall of the seminary and Merric tried to open the window to let it out. The Dean came along and said, “What are you doing with that filthy fly?” He said, “I’m trying to let it out.” The Dean squashed the fly on the window pane. Merric apparently flew into a rage and told him that he’d committed a frightful sin in killing a living creature, and that it had every right to exist like anybody else because it was God’s creation. ”

“Merric had been brought up an Anglican. At one stage, he had thought he’d like to be an Anglican minister, but when I met him he was a member of the Christian Science Church. Doris’s mother, Evelyn Gough was, I believe, Victoria’s first female editor of a newspaper, and was a journalist. Evelyn had left the Catholic faith to become a Christian Scientist and brought her children up in this denomination, so when Merric met Doris, she was a Christian Scientist and he became one too. Christian Scientists, as I understand, believe that illness and death are not real. In the family, you really could not talk about illness or death. The children were brought up to avoid these subjects. Death, as a subject, was almost taboo. I can remember being frowned upon for saying something about death and Guy telling me later, “You know my family doesn’t like talking about death. They get upset”. ”

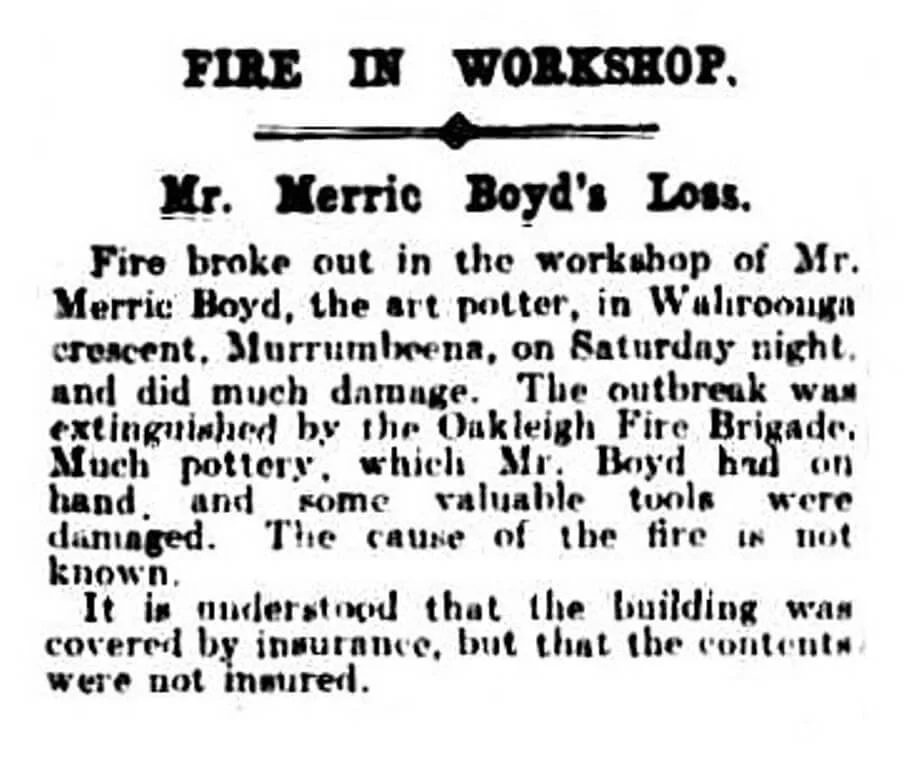

The Argus of Monday, Oct 25, 1926 reporting the loss of Merric’s pottery at Open Country.

Merric was a Teacher

“I was exposed to pottery right from ‘the jump’. When I think about it, I can’t even remember learning to throw. I can remember sitting on Merric’s lap at the wheel whilst he guided my hands over the clay, but as to when and how I even threw the first proper pot, I have no recollection. It was a natural extension of working with my father.

When we were toddlers, too young to get on the wheel, Merric would give us little pieces of clay. His power wheel was beside a window. We used to stand on a box outside the window. He’d cut the rim off the pot to even it up, like a long liquorice strap, and hand it to us. We started modelling and shaping things with the clay that Merric gave to us this way. It’s the earliest recollection I have of actually using clay to make things. He taught us how to press vine leaves into clay and cut out the profile, and how to model little animals, and simple little things like that. We’d then make our own inventions in clay, and he’d fire them. ”

“When he taught us how to throw pots, he never offered a criticism of anything we made. His view was that everybody should be encouraged. He would offer technical advice, but never criticism of the idea that we were attempting to convey. He was a teacher in the best sense. He taught by example and by giving us the right materials to use.

Merric always praised whatever we had done artistically. He let us take our own direction. I think his attitude was that you should do whatever you are motivated to do, and that you mustn’t do something in a creative way because someone tells you to do so. I think he had a pretty sensible approach in that area. ”

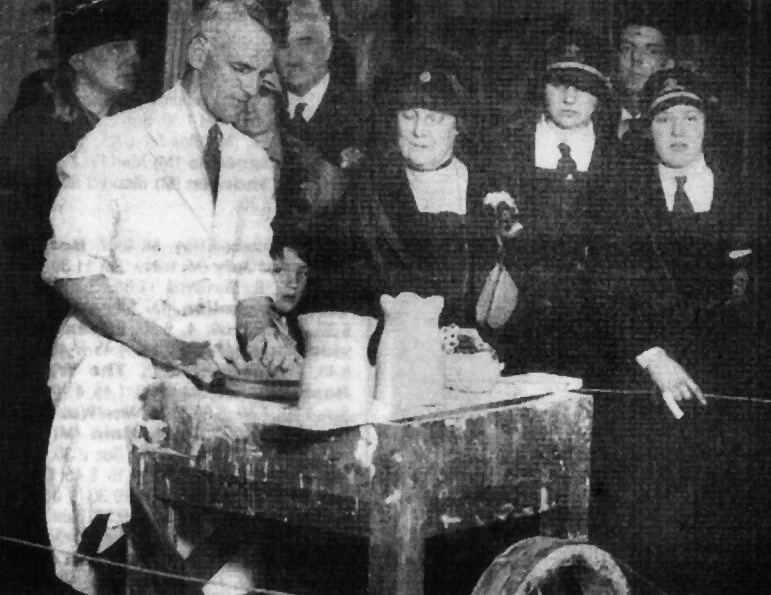

Merric giving one of his many pottery-making demonstrations. This one is at the annual exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria in October 1929.

Merric was Dedicated, Committed, Resilient and Hardworking

“Daddy’s kiln went ‘bung’, and he used to take his pottery to Oakleigh for Hatton to fire. He was desperate to get his stuff fired. Hatton said to me, “You’ve no idea how hard he worked”. ”

“I think that Merric would have been a very attractive young man in his early days, when he first came to Murrumbeena and was ‘batching’. On the corner of Hobart and Neerim Roads was a grand old home, with a considerable amount of land around it. I met a woman who was the daughter of the people who had owned it. She told me that Merric used to visit them there, and attend their parties. Talking about her sisters and herself, she said, “We all fell in love with Merric. He was so dashing and courteous and energetic. He was such fun and so witty.” They all loved him. He wouldn’t have been much more than twenty, and a handsome young man. I was delighted to hear all this. ”

“Merric was incredibly vigorous. If he could run, he would, rather than walk. ”

“Merric was a very hard worker. His kiln was coal-fired with double fireboxes, and sometimes he would stay up all night, stoking, and looking after it. One morning, he was stoking the kiln and he suddenly collapsed. I couldn’t have been much more than six or seven at the time. He was standing with his shovel, and suddenly he just keeled over onto his back. He’d probably been up for about twenty-four hours. Whether he had an attack or not, I don’t know. The coal fumes may have overcome him on this occasion, as well as exhaustion. I ran back to the house, and then out to the road, calling for help. The Jordans lived across the road. Mr. Jordan was a quiet and pleasant man, and strong. He rushed over. He picked Merric up, carried him into the house and put him on his bed. He recovered. ”

“Merric was very brave. He never complained about anything, including about how he was in himself. I think he would have pushed the idea that his health was in decline from his thoughts; I don’t think he would have accepted it. The condition of his health has often been overstated in things I have seen and read. The focus on Merric has always come back to his epilepsy. His epilepsy wasn’t the main point at all! It was purely incidental to his total creative life! Usually, his attacks were quite mild; he might become unconscious, but more often than not, he’d come through them without losing consciousness. If he was getting to this stage, he would say quite distinctly ‘I’m pegging out’, which is used as a metaphor for dying. He never did; the epilepsy itself didn’t kill him, but it does suggest that he accepted it as being part of who he was, one way or another. I don’t think he let the epilepsy get on top of him. I don’t think it could have really; he wouldn’t let it. Whatever effect Merric’s health might have had so far as the development of his imagery was concerned, such as the tortured figures and tortured tree forms and shapes, I couldn’t say. Whatever it was, it never affected his vigor or his tremendous energy. He continued to work. ”

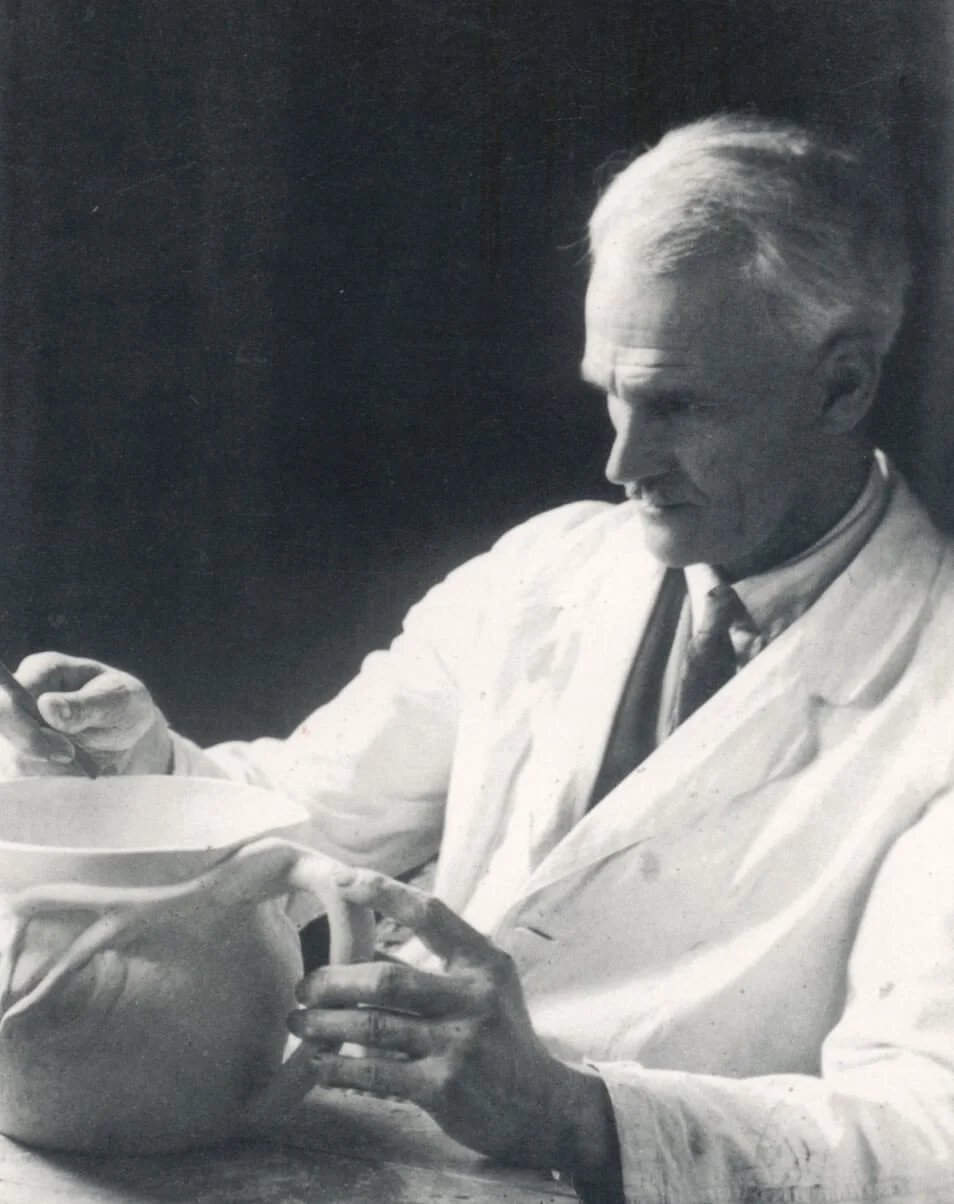

Merric Boyd c. 1930.

Merric knew Guilt & Self-doubt

“He had great difficulty making money and coping with the outside world. Doris had to continually fall back on his parents for financial support. Supporting five children is hard work and I think he found that hard to cope with. Lucy said that he told her that he felt he hadn’t been a good father. I think that must have been a tremendous worry to him, that he really couldn’t support the family. I think also he must have been conscious of his fits by the time it was getting into the 1940s. ”

“He also would have felt he was being judged by others, certainly by Aunt Letti. Aunt Letti was Doris’s closest sister and could never get on with him. Doris was the youngest in the family, and Aunt Letti the second youngest. She lived in Malvern and by the time I came into the family, was coming over to Murrumbeena and would have a cup of tea in the bungalow with me. She loved Doris. They’d been very good friends and kept up their friendship. She was a very direct person and she just couldn’t hide it. I think that was partly why Doris didn’t want to see her too often in the end. I think she didn’t want to be made to feel critical of her husband. I think that would have made him feel even more guilty. I think too, he didn’t really have much contact with the boys as they grew up. He must have known he was shutting himself up in a world of his own. ”

“I think that because he often felt he had been a failure, he wanted people to know that he was an artist and that he did have this talent. Occasionally we would take Merric and Doris for a drive. Doris loved getting out. I don’t think she cared where she went, as long as she went. We’d take them for drives or have them over for dinner because we were still living in our old house in Oakleigh. I don’t know why, but we often drove through Frankston and down the coast. We went up to Yarra Glen once. It picked Doris up, and I think Merric quite enjoyed it. I remember once we drove somewhere down the coast. We stopped to get some ice-creams and we couldn’t get him out of the shop. He insisted on getting out of the car when Guy went in to get the ice-creams and talking to the lady. She was standing there looking a bit bemused as he started off with his usual thing saying, “I’m Merric Boyd. I’m Australia’s first art potter”, and I think he told her about Wedgwood and how he’d worked for Wedgwood. He was shaking her hand and telling her she was a lovely lady. So really, if he had someone else to talk to it was quite good. ”

“He was tormented by his demons, whatever they were. They probably related to him being so deeply religious, and his capability for anger. This aspect of his nature too, has been overstated. He was outspoken in so far as that if he was at a gathering and believed that someone had caused offence in some way, he wouldn’t shrink from roaring the tripe out of them. But then, five minutes later, he’d be begging their pardon, and giving an apology. You get the impression he was volatile all the time and he certainly wasn’t. ”

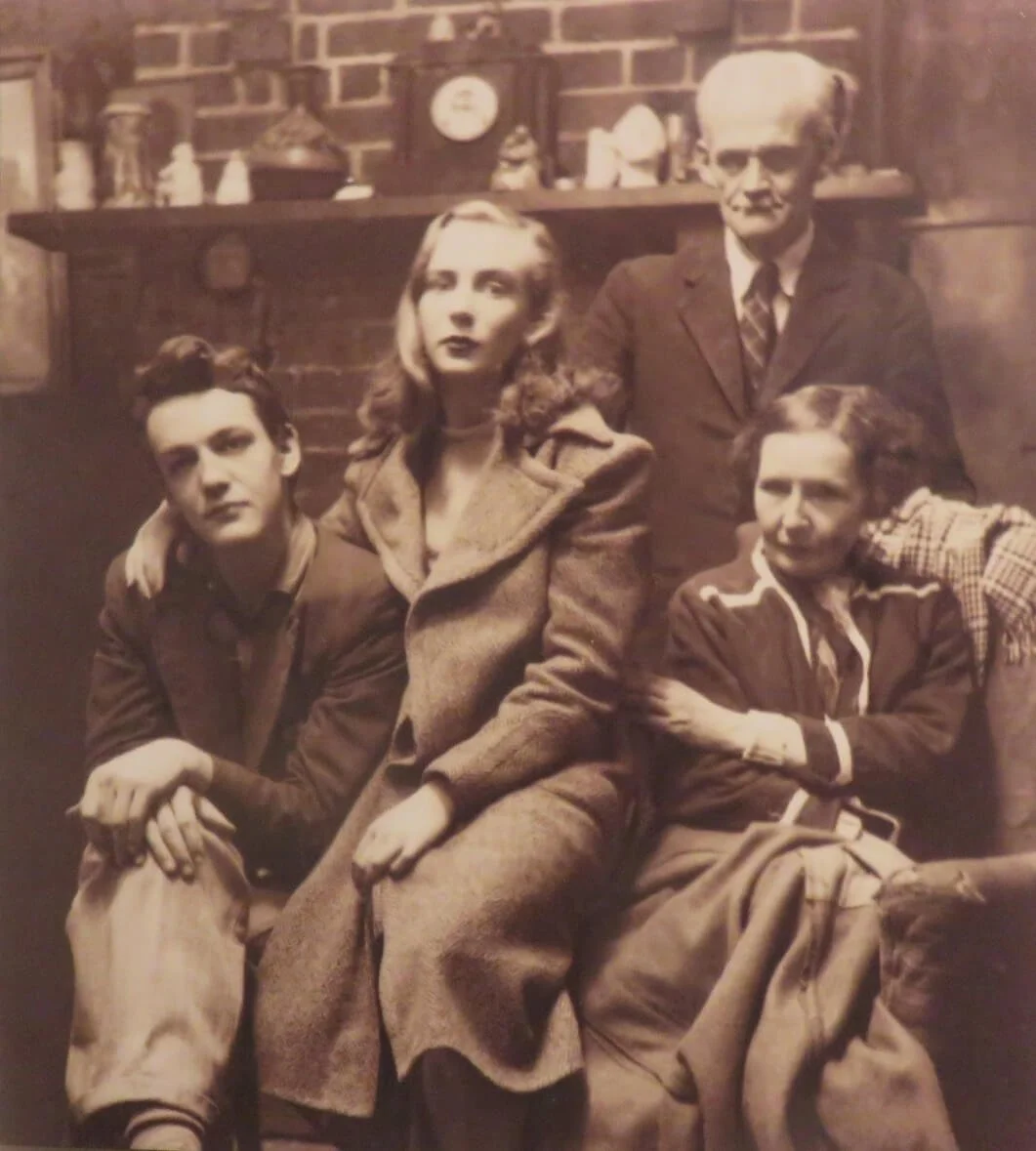

Family Photograph at Open Country. From the left are John Perceval, Mary Boyd, David Boyd, and Merric and Doris Boyd c. 1944.

Merric could be Strict and Demanding

“He was very strict in some ways, especially when it came to social behaviour, and would always instruct us in these matters. He used to say things like, ‘If you haven’t anything kind to say about somebody, then don’t say a thing’. He was pretty good by way of his own example. ”

“He was volatile and quite impossible at times, but at the same time he had this compunctious side to him. He wasn’t terribly strict, but one of the things he believed in and was very strict about, was the way we spoke, and the language we used. At any suggestion of the vernacular, he’d be down on us like a ton of bricks; we couldn’t even say ‘damn’. It angered him when we came home from the local state school with, naturally enough, a flat vowel sound. I can recall many times being stood up against the wall of his studio and be made to recite the vowels, and things like ‘How does the cow go around the pound?’ If we got too extreme or ‘nice’, he’d say, “You don’t have to put on side. Take the marbles out of your mouth. This is not elocution, this is enunciation”. Consequently, as lads we had a reputation as having nice speaking voices. This was largely due to Merric’s insistence; otherwise I imagine we probably would have ended up with the ‘dinki-di’ twang. ”

“Merric was a very gentlemanly man, even though he sometimes had a frightening temper which could alarm people. He could be quite frightening when he lost his temper. ”

“Guy remembers Merric as being a very strong disciplinarian when they were growing up and that he didn’t leave everything to Doris. He thought that he had brought them up to be well-mannered and well-spoken and to respect women and respect their mother. Merric hated having to get cross with them. Sometimes he’d take a branch off a tree and they’d think, ‘Oh, he’s going to give us a beating’. Then he’d beat his own leg. They’d be so upset that he’d done this. He did things such as always correct their speech because there was a proper way that had to be spoken. ”

“He could be very impatient, but he was never volatile in an aggressive physical way. He’d shout sometimes about something when he was angry; if for example, there was something that he regarded as a cruel or unkind act. He never got angry with people because they didn’t do whatever they were supposed to be doing the ‘right’ way. ”

Family photograph of members of the Boyd family at Open Country c. 1944. From the right is Doris, Merric, Mary and David Boyd. The impact of years of epilepsy can be seen in a prematurely aged Merric Boyd. In this picture he is only about 55 years of age.

Merric was Creative

“All I know is that he had areas of great torment as well as tremendous energy and great creative strength. If you look at the texts that he wrote on many of his drawings, he talks about a creative life and creative purpose. The creative idea to him was paramount. The creative spirit was the source of everything. Using the natural world as his vehicle, he’d translate it into whatever direction it took him. What I observed, years later of course, was the incredible sense of pain and torture and agonizing imagery in many of his trees. He must have suffered terribly. ”

Merric, Doris and Yvonne Boyd on Port Phillip Bay c. 1950. Merric has his drawing pad with him. With them, from the left, are Polly Boyd, Matthew Perceval, Tessa Perceval and Jamie Boyd.

Merric was a Pacifist & Respectful of life

“For Merric, killing anything was just not done and that’s all there was to it. He was really extreme in this respect. His interpretation of the testaments and books of the bible would have been quite different from an orthodox one.

Although Merric used to talk with enthusiasm about Australian life, this was more to do with the environment itself and his sense of belonging to it. As a consequence, for him the idea of killing anything was just the most awful thing a person could do. My mother, of course, also had this view, but Merric was emphatic about it. It was indoctrinated into all of his children from infancy. He insisted on the ugliness of guns. He used to say, “Guns are ugly things”. We weren’t even allowed to point a finger and say ‘bang’, or play Cowboys and Indians. If we did, we’d have to do it when he wasn’t looking, because if he saw us, he’d say, “You are pretending that is a gun and that you’re going to kill somebody”. He was quite fiendish about this sort of thing. I suppose if you grow up with this, you’ll hardly applaud the idea of killing anybody or anything.

For Merric, even the killing of snails was abhorrent, and now, when I see a snail on the footpath, I’m compelled to pick it up and put it to the side, because Merric encouraged us to do this. I remember Guy, Mary and I once came across a bed of red-back spiders in the shed behind the pottery. I knew that red-backs could bite and make you sick, or even kill. We told father about them because we didn’t know quite what to do. Merric let them crawl onto his hand. He took them down to the bottom of the garden and put them on the ground. He had no fear of them, I think because of his intense religious beliefs, and his abhorrence of any kind of killing. Whilst we weren’t vegetarian, I remember on a couple of occasions when we were having a meal that included rabbit, my mother would tell Merric that it had a rabbit flavour or something, but that it wasn’t an actual rabbit. I don’t think he was consciously vegetarian, but he did have this abhorrence of any kind of killing.

My father was like a prophet in a way, yet while he had these views on killing, he didn’t really preach pacifism as such. I don’t think he even used the word. ”

“Merric and Doris were pacifists. I once asked Doris to explain her pacifism. She said it was very simple, she did not want her children to be killed or maimed. ”

Merric Boyd c. 1953.

Merric had a sense of Humour

“He had a wit too. He always used to travel second class, and his relatives always travelled first class. Somebody asked him why he didn’t travel first class. He said, “Because there is no third”. ”

“Merric had a great sense of humour. An example of his capacity for fun and humour was when I was going to a boy’s birthday party when I was about ten years old. He gave his usual going-to-party advice about always being polite to ladies, and always offering them your chair and so on; the usual sorts of social niceties. Then he said, “If you are kind and nice to people, you’ll find it pays”. He used to say this sort of thing quite often.

On this occasion, I said to him, “Is it alright Daddads to be nice to people if it doesn’t pay?” His face darkened over. I thought he was going to march me over to the plum tree, which he used to do. He’d take a twig from a branch of the tree, clean the leaves from it and make a switch. Then he’d roll up his trouser leg and lambaste his leg. “See what you’re making Daddads do. You’re making him punish himself”. That used to be his phase. This was a bit perverse to say the least. Whether there were Freudian overtones to it, I can’t say. Not that it happened every day, but after a time I knew what I was in for and I would be very pleased. At least he was going to hit himself and not me, but he wouldn’t stop until the blood started trickling down his leg. Then inevitably, as a small boy, I’d beg him to stop. It was a strange perversity, but it illustrated a facet of his temperament; he couldn’t bear to strike any of his own children, but he felt he had to try and force a lesson home.

On this occasion, I thought I was going to be marched off and go through the whole routine. All of a sudden he started laughing. He said, “Oh that was splendid Wunky; that was very good.” Wunky was his term of endearment. What he meant by pay was that it paid in terms creating a more harmonious situation, and not in terms of money. He didn’t mean to say that you would get sixpence because you were being polite, but to a kid, naturally enough, you think in terms of being paid for something. This illustrates a facet of his temperament. He had a sense of fun and humour, and he wasn’t stubborn when he saw child making an observation such as I did, or asking that question. ”

Merric was Inventive

“ He was pretty ingenious in the way he invented things. He made his own power wheel. He devised a method of running a long belt from a donkey engine to his wheel, which he designed himself. This was his smaller wheel, which he used to throw small pots on very quickly. He also had a larger kick-wheel, which was on a large frame. ”

The hands of Merric Boyd as they glide across clay in the 1920s.

Reflecting on Merric, I think that his essential personality was, more or less, the same as the rest of us. A little eccentric perhaps, but for many creative people, this isn’t unusual. But there were two aspects of Merric that were significantly different. The first was his sensitivity to clay, both physically and as a medium to express himself creatively, which was unparalleled. Make no mistake; there is genius in his pottery and there aren’t too many geniuses around.

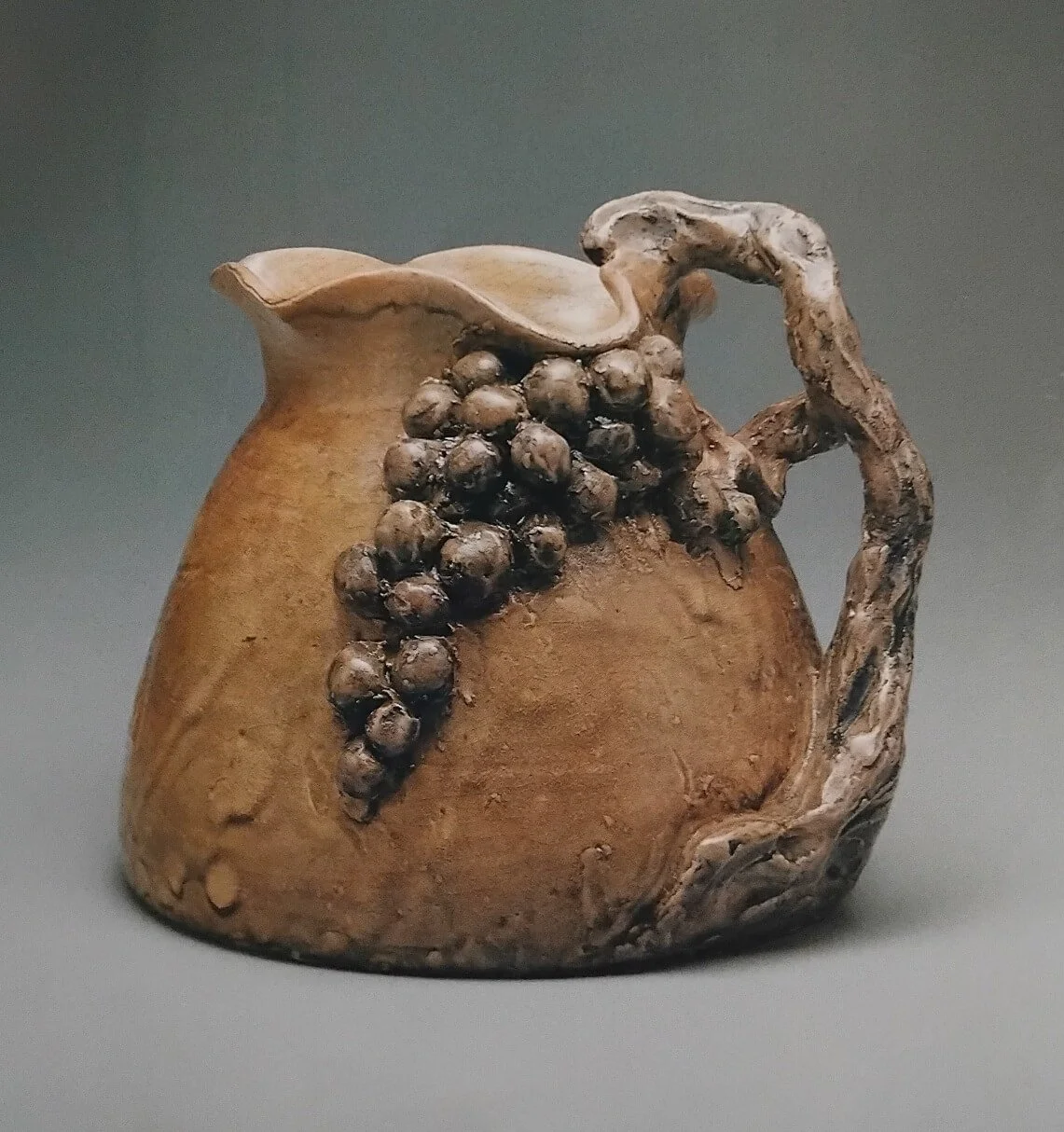

Jug, 1915

The second was epilepsy. This condition never defined him; his art did. But this being said, it had a profound impact upon him and his family. His physical, mental, social and emotional health all suffered, and it aged him terribly. It caused him to become often reactive, frustrated, and impatient, and critically, unable to reflect on his own behaviour. Had he not had epilepsy, his health would have been infinitely better than it became. What is so very impressive about Merric is that he continued to be creative to the end of his life, despite his deteriorating health. Above all else, it is art that defines who Merric Boyd was.

Jug, 1926

Phyllis Boyd was right when she spoke of a sad dimension to Merric’s life. What gave him this was epilepsy. The man she met in 1952 was worn out by it. He was tired and unwell. And towards the end of his life when he was taking medication to reduce the impact of the seizures, it sapped him of his remaining vigour and energy, and eventually killed him. Had he not had epilepsy, he wouldn’t have been the person that Phyllis knew. He would have been someone else, and that person would have been, in all likelihood, a lot happier and healthier, and lacking the sad dimension she spoke of.

Jug, 1931

A harder question to answer is as to whether Merric lived the sad life that Phyllis felt he had. How do you define sad and a sad life? Does a life of extreme highs and lows constitute a sad life? Is it a matter of proportion; does 30 % of life spent being sad constitute a sad life? Or 40%? Or 50 %? Is a sad life something that can even be measured? Merric had epilepsy. Does this mean his life was sad? Is it for others to say whether Merric’s life had been sad or otherwise when only he could really know?

Lamp, 1931

In the 1910s and 20s, Merric established himself as a potter of renown and became very well known for it. He gave pottery demonstrations at city stores and elsewhere. His special pots were expensive and sold well from prestigious shops and department stores. The Argus called him ‘King of the Melbourne Potters’. And in these years, Doris gave him five children, bringing him enormous joy and satisfaction. Life was rich and satisfying.

Then, in 1926 when he was 38 years old, his pottery burnt down, this severely curtailing his ability to make and sell pots to generate an income. Soon afterwards, he had what is generally considered a nervous breakdown. He also had the first of the tonic-clonic seizures that plagued him for the rest of his life. If this wasn’t enough, The Great Depression was soon to arrive, as was a change in market taste that saw fine China pottery come into favour. In the space of a few years, his fortunes changed completely. Whilst he continued to make and sell pottery, he never fully recovered from the fire and loss of his pottery, and he was never able to draw the income that he once had. Life was not so good.

Pot, 1932

Merric’s life can be broadly divided into two halves: before and after the fire. Did the fact that the first half was so successful and the second so challenging make his life a sad life. I’m not so sure. The challenges he faced, both personally and professionally were great, but not unique to him. They were life challenges, the impact of which were magnified by epilepsy.

Kookaburra, 1935

Many of the years Merric lived with epilepsy were filled with creativity, art and family life. He didn’t stop being happy because of epilepsy, though in his last years, he was exhausted by it. Through the late 1920s and the 1930s, Merric made some of his very best and most iconic pottery. He had established his method of its making, combining wheel thrown pottery with strong sculptural elements, and was broadening and deepening his approach to it. He was throwing pots as late as the early 1950s. His late period works, whilst rawer and less refined than earlier ones, all carry the same sincerity, honesty and integrity as the earlier ones.

Teapot, 1946

And he was drawing the world as he saw it, incessantly. His subjects were wide ranging and included family members and others, animals, houses, clouds, trees and forests, and streetscapes. He drew images of Port Phillip Bay on family outings and holidays there, and from his past, especially from his time living in the country. On these drawings he would frequently write what amount to joyful affirmations of life, often with a strong spiritual dimension.

One reads:

Always

Perfect Love

Have Now

Merric Boyd

Another reads:

I am Merric

Boyd held Through

All Eternity Here and

Now Love Governs me

‘Love Governs’ was Merric’s favourite maxim and is found on his gravestone at Brighton Cemetery. These words do not paint a picture of a sad man. Rather, they tell of a man who is happy in his internal world, and quite possibly done with the outside one.

Tree, n.d.

Bird, n.d.

So much of Merric’s happiness was derived from his art; it was there that he both lost and found himself, immersed in the act of creating. And it was derived from his marriage and children. He and Doris successfully raised five children who grew into talented and creative adults and who gave their parents their love and support. For Merric, they were a source of joy, and creations to be celebrated.

Trees, 1942

Considering the totality of his life, I think that Merric achieved too much in his 46 years at Open Country and had too many celebratory moments to call his life a sad life. It may not have been an entirely happy one, but it was loving and creative, and that’s a very good start. Perhaps I’d call it an interesting and challenging life, and settle on that.

In life, Merric was dealt some pretty interesting cards. To be born with a brain with so much creative ability and with that same brain prone to epileptic seizures. A brain that gave so much and took so much. I wonder if, in a parallel universe, Merric had a choice: to be born with both the creativity and epilepsy or with neither, which would he have chosen. I don’t know.

Hillside at Sunset, 1949

*All Photographs courtesy of Boyd Family Archive

*All quotes from interviews with Colin Smith.

Lucy Boyd Beck: 1997 & 1998

David Boyd: 1997

Phyllis Boyd: 1989

Joan Linton: 1989 & 2003