Lessons Learnt by an Unlikely Self-Taught and Self-Published Author

I’m one of the last people destined to write a book and become a (self-published) author. At primary school, I didn’t like reading. It was only towards the end of those early years of education that I found a series of books that I liked. They kick-started my reading. For a space-obsessed kid, the books of British writer, Hugh Walters, which carried cheesy titles like Journey to Jupiter (1965), Mission to Mercury (1965) and Spaceship to Saturn (1967), worked for me. They may not have been high literature, but 30 years after his death, they are still available. There’s something in that.

At secondary school I was an average student. Keep your head and hand down, don’t get noticed, don’t volunteer for anything and don’t stand out. Sport was good, and in the classroom, social studies was interesting. I liked geography and history because the teachers were good and made the subjects live. My maths skills were poor and I dropped from the subject as early as possible. I was a terrible German student. I just didn’t have the ear for it and Germany meant nothing to me. I didn’t even know where it was. I was taught by a teacher from the north of England who spoke in an accent you’d expect him to speak with. In year 10 he advised my parents that I should give the subject away. This was good advice. Ironically, only a few years later, I found myself working on a construction site in Massing, about 90 kms east of Munich in West Germany. Despite my worst efforts, it was amazing how much basic German had stuck.

This Bell and Howell tape recorder is the machine I used to record the many hours of interviews for Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena. It’s also the one I used to transcribe them. That’s thousands of cycles of record, pause and play. A fantastic machine and a real statement about its quality.

Despite having some good teachers, I didn’t like English and thought the conventions of grammar to be boring and unnecessary. I was no good at art and dropped it as soon as I could. Despite everything and to my amazement, I attained my Higher School Certificate (HSC), managing two Cs, two Ds and an E. (I was no good at biology either.) I remember staring in disbelief at the paperwork telling me I’d passed. And with that I scraped into a primary teaching course at Burwood Teachers College, now part of Deakin University, on Burwood Highway.

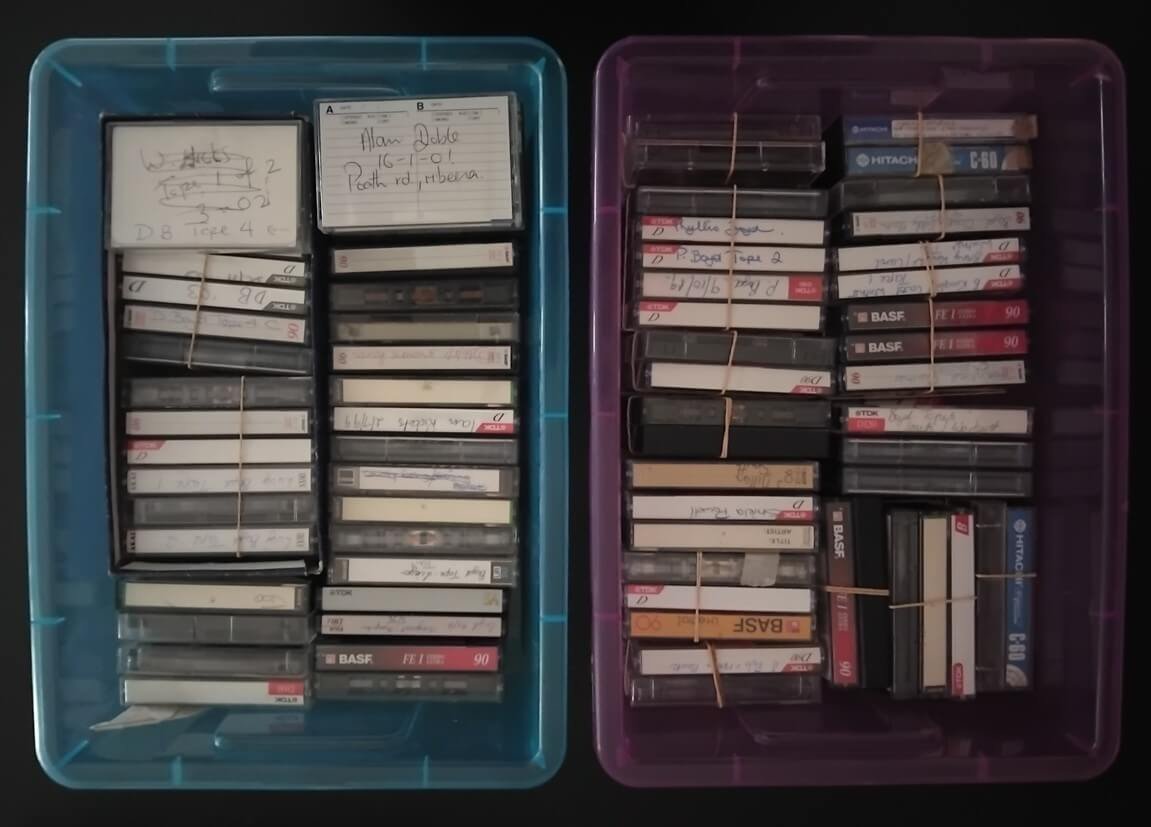

Some of the audio tapes used to record the interviews used in Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena.

All this is a way of saying that whilst you may not appear to have a lot of academic aptitude, you can surprise yourself. What you’re like at one stage of life can look and be very different to what you’re like at another. You just have to find your thing. Your thing is the thing that interests you beyond other things. It quietly grabs your attention and nags you to attend to it. It’s what you prefer doing over watching TV. It gets in your head and has you thinking about it and where it may take you next. It’s the thing that you never feel like dropping, and at some point, make a personal commitment to see through to the end, whatever that end is.

And in its own way it becomes a vehicle to travel through life with, like a theme. When you’re sick and tired of the shitty news you’ve been watching and reading about, and decided that the human race is collectively, stupid beyond belief, it’s a distraction and a positive one at that. It makes you feel like you’re doing something constructive and worthwhile.

The thing requires you to find some new ground to work, or an alternative and worthwhile new angle on some old ground. If it’s been done before, why would you repeat it?

I was incredibly lucky because I found my thing. Coming to Murrumbeena in 1983 and becoming involved in a campaign to save a local park started me on a course of recording the Boyd family’s history in that suburb. That interest broadened to include the Boyd family beyond Murrumbeena and Murrumbeena history in general. Over 35 years later and at this point in time, I think my thing might be done, but that remains to be seen.

Another view of the tapes. There are many more than this. These tapes will shortly be donated to the State Library of Victoria.

When I started recording the stories of people who lived in Murrumbeena and their memories of the Boyds, all I knew was that I was going to do a book on what I learnt because I knew that the material was interesting. As I tracked down the 50-odd people whose stories are in Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena, all I told them was that I was researching the Boyds with the intention of doing a book, because that’s all I knew. This meant that I had committed myself to doing it.

In researching and writing my books, I made every mistake that it’s possible to make. I have something of a DIY attitude, which means that I’d rather find out myself and do it myself rather than being told or following someone else’s instruction. Consequently, I had to make a lot of mistakes before Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena was published. The down side of this approach was that I wasted a lot of time fixing what I’d messed up. The upside was that I learnt from every error I made and I didn’t forget any of them. Also, it meant that when the book was finished, it was all me; the good bits and the bad.

What you learn from doing one book is the very best reason to do a second. You learn so much, from beginning to end, that it seems like a real waste not to do another. After the first book, you know 90% of what to do for the second, and the 10% you don’t know is easily learnt. Try doing a third and fourth book. It’s work, but it gets easier still.

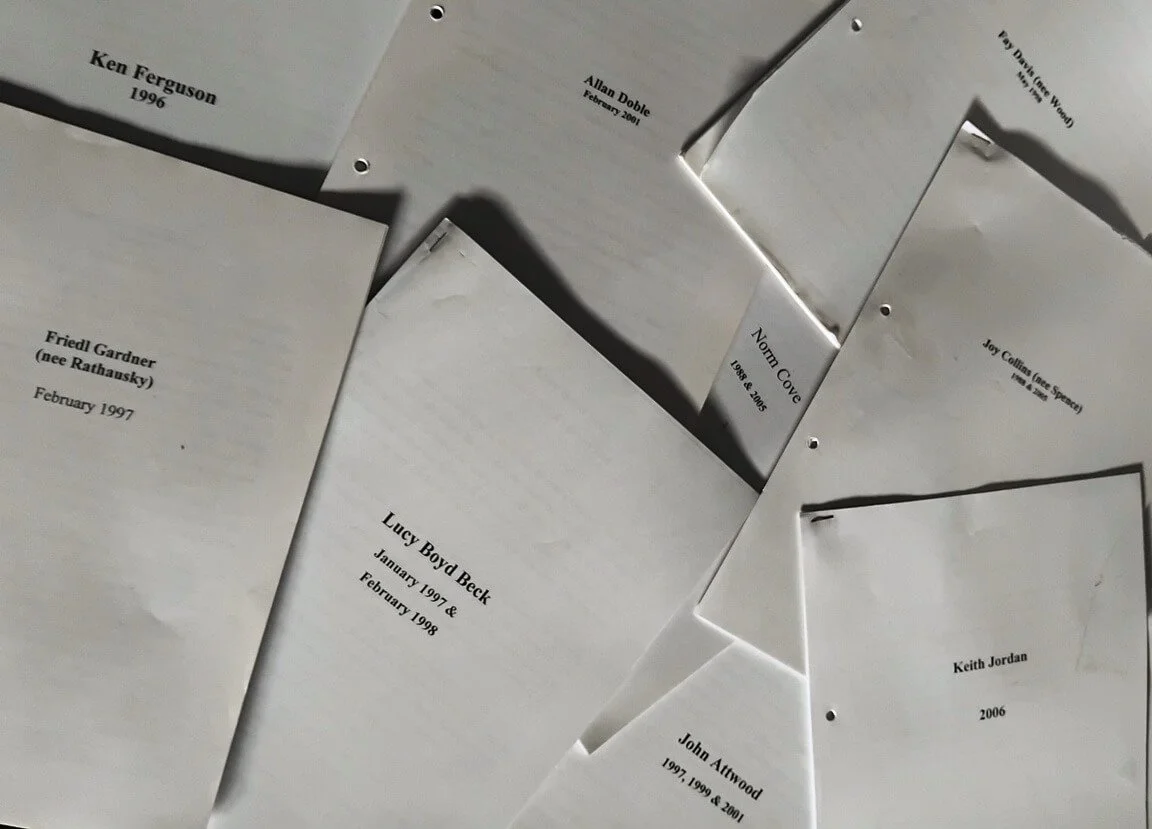

After the tapes for Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena were transcribed by me, they were typed, in the early days by others, and later on by me. These are a handful of completed transcripts.

With all this being said, the following are some things I’ve learnt about producing a book. If this is useful to someone contemplating this or a similar project, well and good.

*You have to be dedicated. Not driven, but dedicated. If you’re not, if you’re only half committed to the task, let it go now. It’s not failure. It’s just deciding where you want your time to go. And if it’s not a book, it may very well be something else.

*You have to be relentlessly motivated. Following on from the above, motivation is everything. Got a spare half hour; do some book. It’s like a muscle. Work it. Keep the project moving forward. It may ebb before it flows, and ebb again. Whatever it does, keep it moving forward, even little by little. And if you stop and don’t really feel like picking it up again, it may not be for you. See what you do.

*You have to believe in your project. If you don’t, it will sap your motivation and probably kill it. The prize is finishing it, and in the end, holding your book. It’s a real blast holding your first book. Should you do more of them, they will be satisfying too, but they won’t be like the thrill of the first.

*You know you’ll have to spend some money. The main expense of a book is your time and you don’t pay for that. Depending on the project, you may have costs such as printing drafts, paying for copyright, reproducing images and the like. If you pay someone to do the layout of your book, it will be a substantial amount. This is what I did as my layout skills aren’t great and I didn’t have the time. To get an idea of the book layout you want, look at books in your local library or bookshop with the sort of content not dissimilar to what you’re doing and draw on the best of them for your project. Do you want hard or softcover? Landscape or portrait? How many pictures do you have to place? Colour or black and white, or a mix of both? Will they need to be placed in-situ where they are referred to in text, placed together or scattered across the book? Are they large or small pictures? Where will the captions go? What type of paper do you want to use? What is the page layout to look like? Wide or narrow margins? How much can you afford to spend in printing? It’s all down the track, but it’s good to get a feel for it early.

Files for Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena. These contained, amongst other things, transcripts of interviews, consent forms, letters, photographs and drawings, all of which related to each interviewee.

*Do your best and don’t cut corners, because you may regret it later on. In terms of quality, aim for perfection, and if you’re lucky, you might get good or even very good. If you’re looking to get your book picked up by a publisher and/or distributor, anything that looks half-finished will likely sink your chances. It has to look great. After all, the world of books is a packed field. You have to look great to be noticed.

*Always aim for a tight script. No flab and no waffle. If you can say what you want to say in 7 words, don’t say it in 9. If something seems irrelevant or out of place, odds are that it is. It might be a brilliant sentence or paragraph, but if it doesn’t have a place, it may well need to go.

*Should you employ someone to do the formal layout of your book, it needs to be a person who gets what you’re doing and you can work with. Every step of the way you will be telling them what you want. If an issue comes up and there’ll be a thousand of them, you’ll need to be able to discuss it with them. That person will be responsible for making your book look exactly as you want it to. You’ll pay good money to get this vital job done, so choose well.

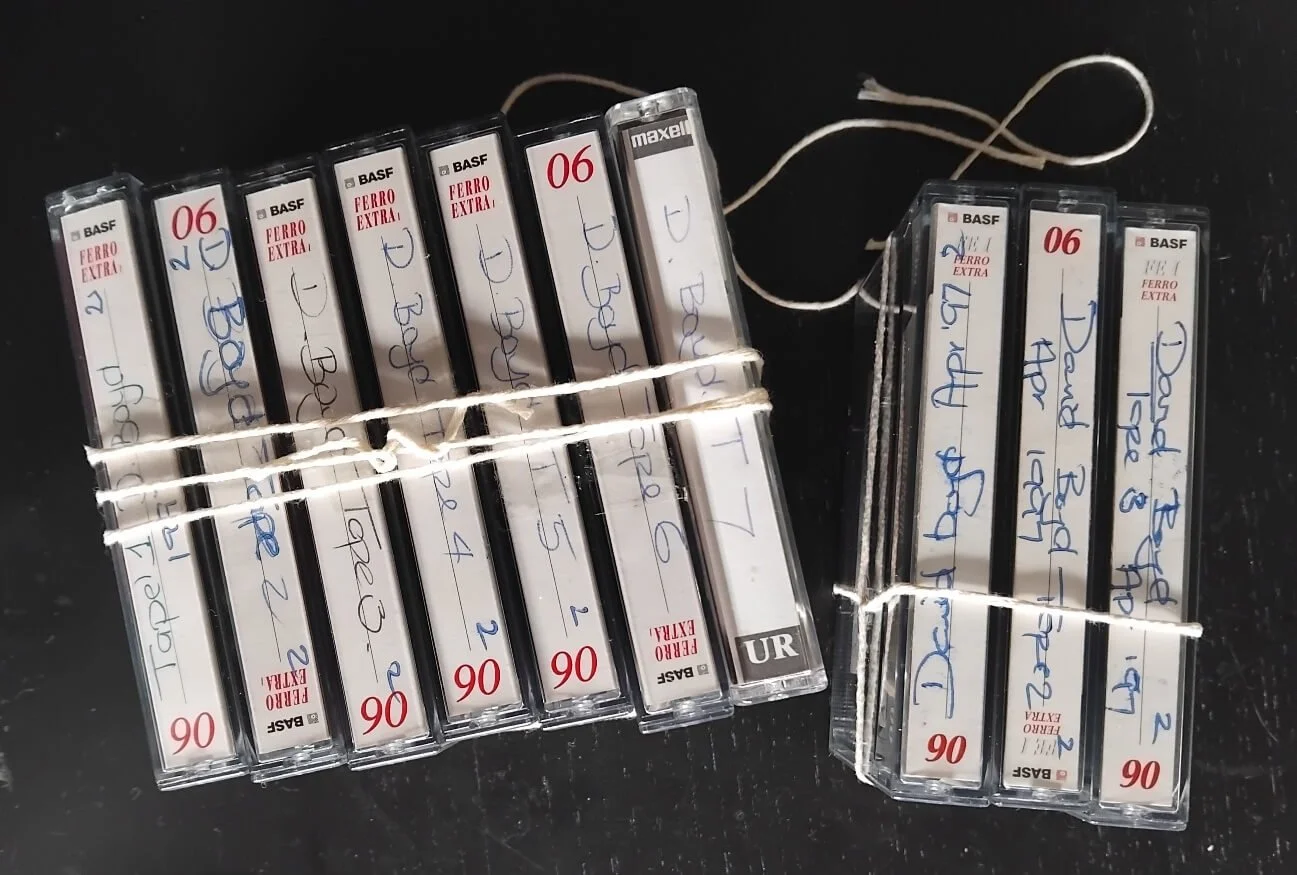

These are the tapes I recorded my conversations with David Boyd in Sydney in 1997. They were by far the longest recorded interviews I did for Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena.

*Get to know copyright law. Whilst I have forgotten much of what I learnt about copyright, I don’t think it’s as complicated as it’s made out to be. Do some internet searches and you’ll learn how it works, who and what it applies to, and what you need to do. Copyright is important to get right, especially when it comes to reproducing art, photographs, newspaper articles and the like. Essentially, what you use will either be subject to copyright or be in the public domain. If it’s more recent and subject to copyright, you need to find the copyright owner (the Copyright Council is a good start) and get permission. If the material you wish to use is older, you may not need to.

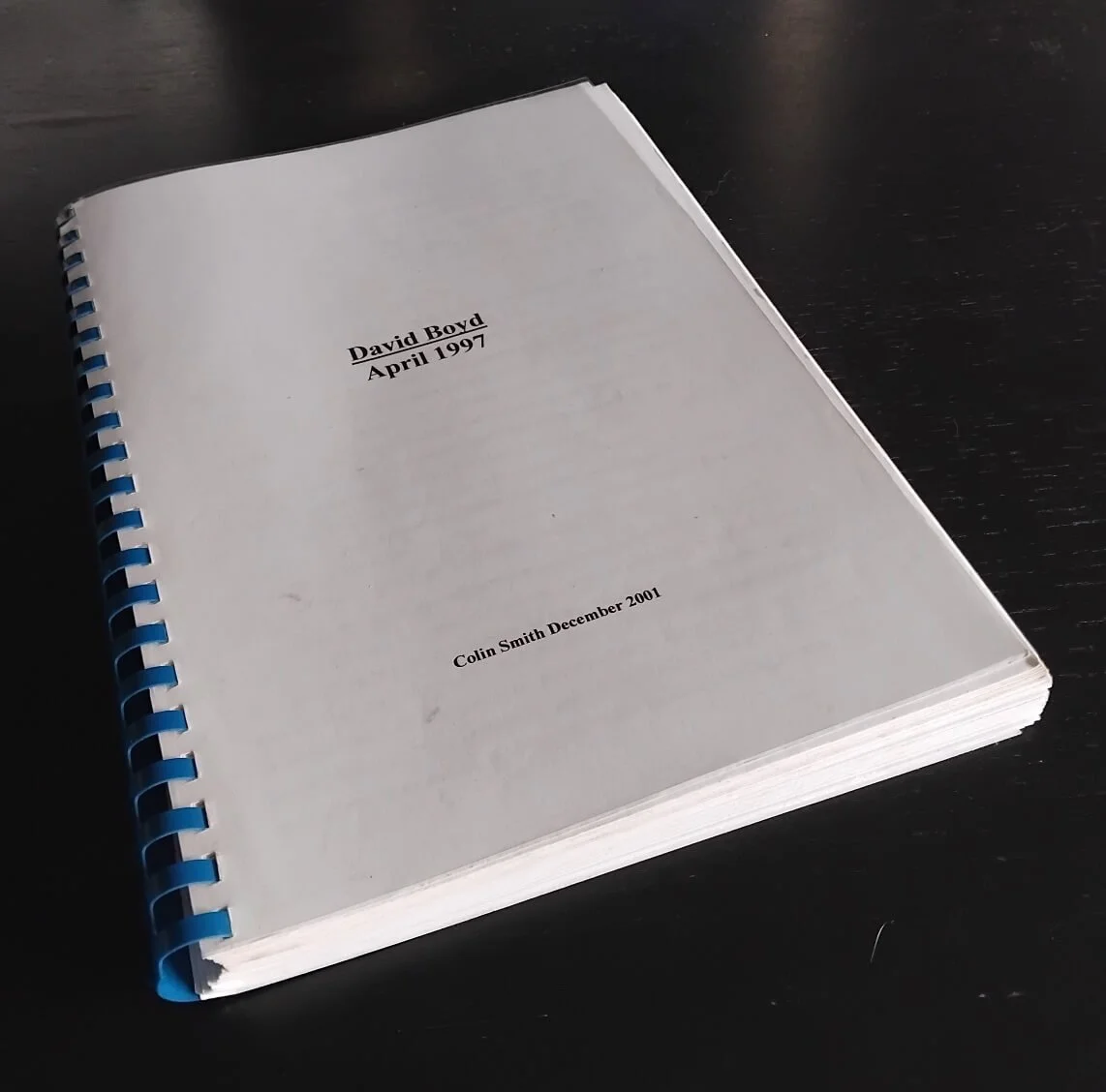

The transcript of David Boyd's interview was so long I had it bound into a separate book before it became part of the whole Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena draft

Copyright isn’t about who owns an image or an object. It’s about who holds its copyright. For example, whilst I may own a painting by Arthur Boyd, I don’t own its copyright and cannot reproduce an image of it for my (hypothetical) Arthur Boyd project. Arthur Boyd’s copyright is held by the Bundanon Trust and only they can grant permission to use it. And separate to this, if a photograph of that work has been taken by another photographer, their permission to reproduce may be needed as well. You need to learn and know your copyright law.

Getting permission to reproduce work that is copyright generally costs. I have found that gaining permission to reproduce news articles essentially always does, and publishers have avenues to do this on their websites. Occasionally you can find some generosity out there, but expect to pay. If you don’t get copyright permission, you’re exposing yourself to potential legal blowback from the copyright owner. Making the effort to learn copyright is important and time well spent.

For the above reasons, there are real advantages in making a project about something or someone from the first half of last century or before. Much of the material you use will be in the public domain and thus be free of copyright. A project on something more recent will require a lot more work and expense to secure copyright permissions.

Keeping track of interview transcripts. When I started Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena, 3 1/2-inch floppys were how you stored and moved data.

*Organize your research material early. Put time into setting up folders and files. I have always worked with folders carrying text and folders carrying images. For images, keep track of where they came from, what they are of and who took them. It may not be a consideration now, but at some point, that information will become captions and credits. It’s hard work knowing all that when you don’t record it.

*Back everything up. One of the greatest fears a writer has is losing work. You may be able to write something again, but it may not be as good as what you lost. And you lose time. My rule of thumb is back-up everything you don’t want to lose, so do it often. Do so on at least two electronic devices as well as your main computer. It’s a lot better to back-up too many times rather than too few. As long as you date your files, you can usually find what you want amongst saved files relatively easily. It’s a lot quicker than creating them again.

A folder of transcripts used for Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena.

*As far as is possible, you have to stay true to your vision and don’t deviate from it. Share your material with anyone who you think will give you worthwhile feedback. The more feedback you get the better, but everyone has to know that you’ll look at what they have suggested, consider it, and keep it or junk it as you see fit. If you think you’ll feel obligated to take on someone’s advice, then don’t seek it.

*Your book needs a really good title and cover. Look at the covers of books you like to help form your own ideas, and experiment with titles. You’re wanting a cover that is strong, clean and appealing. Any publisher, distributor and/or bookseller will tell you this. It needs to get your book noticed. I can’t claim to have come up with brilliant titles, but they have said what my books are about and they seem to have done the job. But importantly, they shouldn’t be vague and ambiguous. The title has to say something pretty clear about what’s inside.

Keeping track of what I’ve got. When doing a book, being organized is everything.

*The more proof readers you have, the better. When your work is getting more finished than started, ask trusted and interested others to read it. Some will read for grammar, some for meaning and some for any other reason. You can’t have too many proofreaders, because errors, big and small, can get into a text and sit there, unnoticed. They are so disappointing to find after your book has been published, and you can’t go back and remove them unless you do a second edition.

Keep re-reading your work yourself, searching for errors. Everything is a potential mistake. In particular check all dates, the spelling of people’s names, and the placement of full stops and quotation marks and the like. Check that each page follows the next as they all should. Check the page numbers. Check your credits and make sure the captions match the right pictures. Check the quality of photographs to make sure they have reproduced properly. Check everything. For A Murrumbeena Scrapbook I had five serious proofreaders who checked drafts more than once. There were others who reviewed sections of the book of which they had a special interest or knowledge. You can’t proofread too many times.

*You’re not in it for the money because there isn’t any. Producing a book will cost money and not make any unless you’re brilliant and produce a best seller. Remember that you’re doing it for the love and not the money. And while we’re talking money, when it comes to pricing your book, don’t expect to recover your costs, because you won’t. Price it so that it sells. A garage full of books is no good. You want them in the hands of the people who will get something from them.

*Every step matters. There is not one weak link in the chain of steps that needs to be taken to see your book completed. Every one of them is a weak spot and every step has to be done to the absolute best of your ability. In my life, I am not renowned for being a perfectionist, but with my books, I am. Remember that if you aim for perfection, you may get very good. In the world of books, that is perfection.

This book was the first time Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena came together as a working draft. From here, an enormous amount of editing was done to clean it up and make it start to look like a book.

*Expect to self-publish. I thought with my first book, Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena that I might find a publisher. There was some interest, but not a lot, and so I self-published. You might find a publisher for your project and if you do, seriously well done, but remember that the financial return you’ll see from book sales will be a trickle, if that. This is because the publisher takes such a hefty slice of the returns from book sales. They do a great deal of work for you and they will arrange distribution, but it all costs. If you self-publish, you cut out this middle man, but it means that you have to publish and distribute yourself. You’ll have to find a printer. And when the printing is done and you’ve got 50 boxes of books in your garage, you are going to have to distribute the books yourself. This is generally a tough gig, especially in gaining access to bookshops. It requires you to make a lot of phone calls and do the leg work, trying to get your book into a bookshop and into the market. The alternative is that you find a distributor to do the job. This way, whilst the retail outlets and the distributor will get their cut of your book’s Recommended Retail Price (RRP), a publisher doesn’t. With this arrangement, a book with a RRP of around $50.00 may provide you with a return in the order of $15.00. It’s at this point that you remind yourself that you’re in it for the love and not the money. Take the loss on each book you sell and get your vision out there.

*If you're getting your book printed, and if you don't have a publisher, you will be, you'll need to find a company to do it. Ask around. There are a lot of printers out there. You need one you can trust and understands what you're doing. Check out their catalogue and see if they do what you are wanting to do. Price matters, but not at the expense of quality. And on price, printing is an expensive business. There are so many variables that will determine your print quote; the number of pages and their size, paper quality, hard or soft cover, and the number of images (including those in colour) are some of the big ones. A minimum print number is generally 500 copies to get a reasonable economy of scale. Any less and your unit cost rises dramatically. Is your book to be glued or thread bound? The latter is more expensive, but preferable for larger and longer books. Print here or overseas? Printing overseas i.e. China may be the best quote you get, but shipping is very expensive, and communication can be difficult, especially if there are issues to sort out (and there will be). Printing here may cost more, but those same issues ought be more easily dealt with. My first 3 books were printed in Singapore and my fourth in Sydney. I was happy with them all, but you need to be prepared to pay real money to get the job done and know that short of creating a best seller, you'll never get your money back. Remember that it's not about the money.

*Accessing bookshops as a self-publisher is challenging. There isn't an agent doing it for you because you're doing it all yourself. Should they take you on, you'll be the one taking the book to their shop and you may well be the one reminding them that they owe you a return for books sold. They may take two or three books as a start. Most will take your book if they believe it will sell. They won't take it if the production values are not high, if they don't think it will appeal to their customers and if it's too highly priced. They, better than anyone, know what sells and what doesn't, and they'll knock you back in a flash if they don't want it. I have found some outlets really difficult to work with and others brilliant. Whatever you're dealing with, be nice to them. Remember, you need them more than they need you.

*Always finish a research session knowing exactly where you’re going to start next time. So much time is wasted ‘faffing about’ (as my northern England German teacher would say). Be organized and use your time well.

*Seek the advice of others. If you can take a few shortcuts using someone else’s experience and expertise, do so. There is an unofficial club of self-published authors out there who have done the journey and will be happy to share what they know. Remind yourself that if it was that easy to do a book, everyone would do one.

*And finally, if this book is really something you want to do, don’t stop. Push it and see it through to the end.